The twenty-first volume of The Tusculum Review arrives at the end of 2025 bearing gifts: writing and art by twenty-five writers and studio artists—teens to octogenarians—with urgent things to tell us about their lives and ours: multilingual ecosystems, ancestral offerings and generational wounds, sore sibling rivalries, atmospheric losses, power in the animal and human kingdoms, poverty and privation, self-celebration in the face of degradation, turnabouts and redemption, open-handed homage to fellow artists, and artmaking while teaching/parenting/drowning. In a nutshell: the weaknesses and triumphs of the body and the soul.

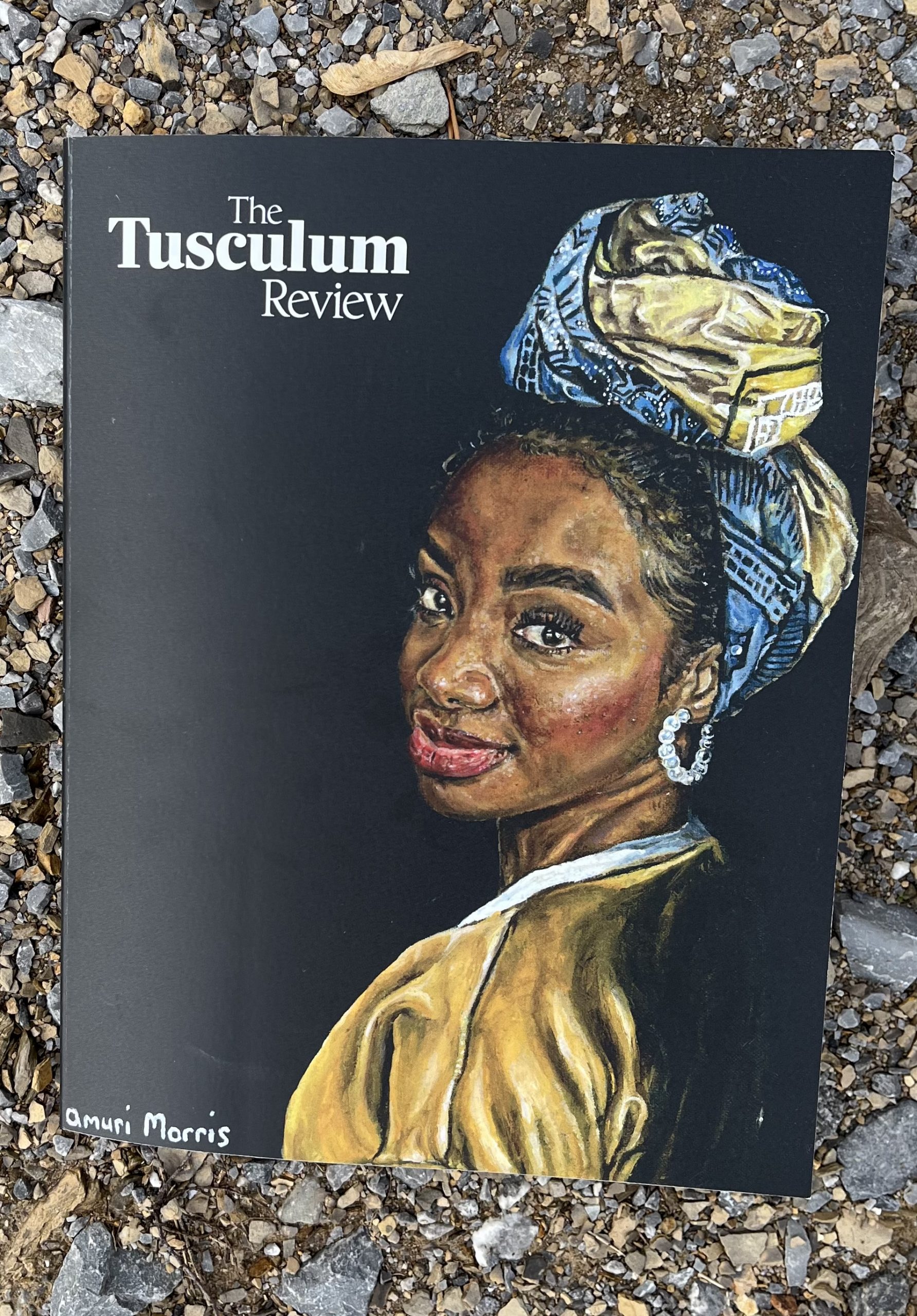

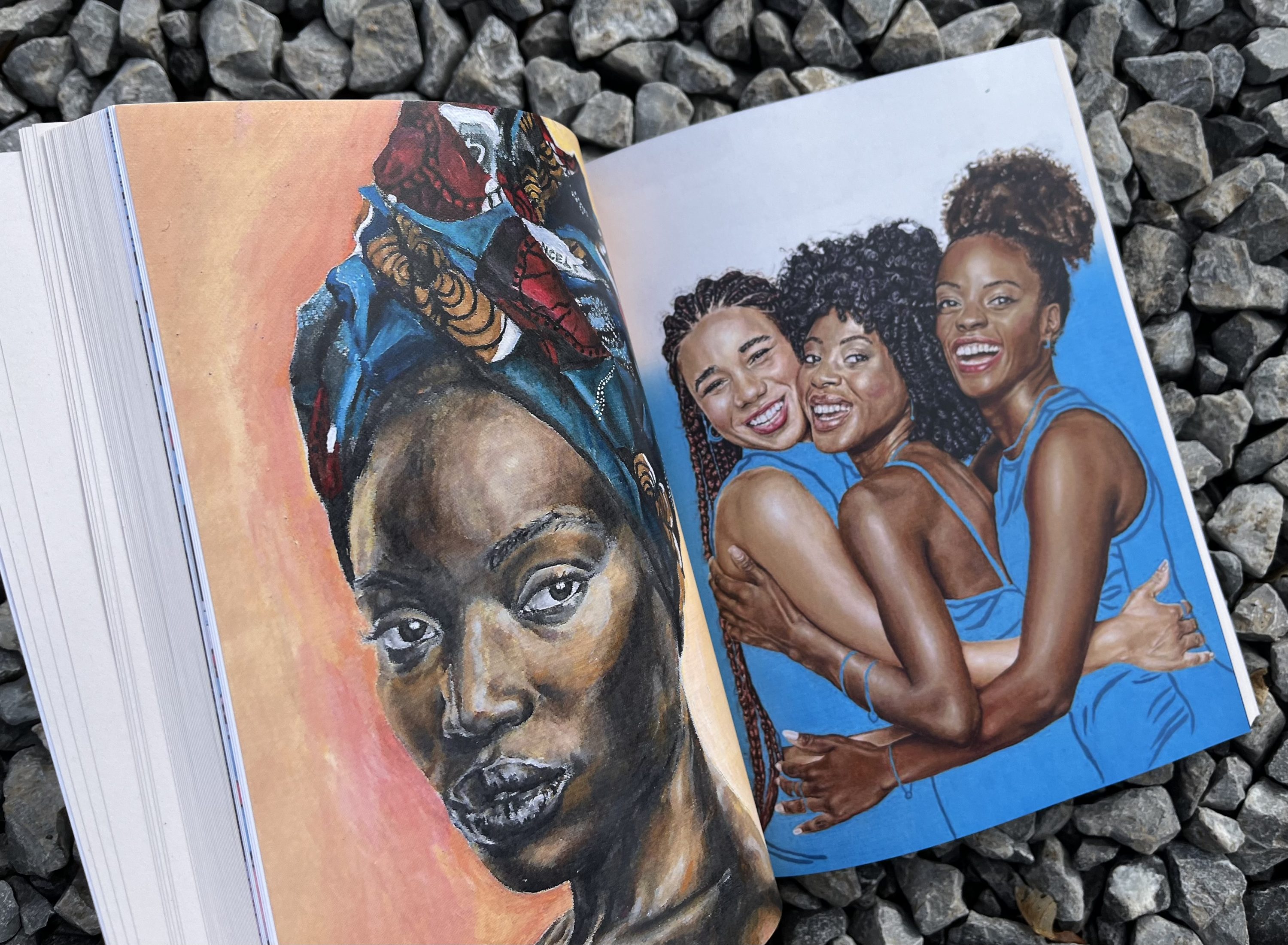

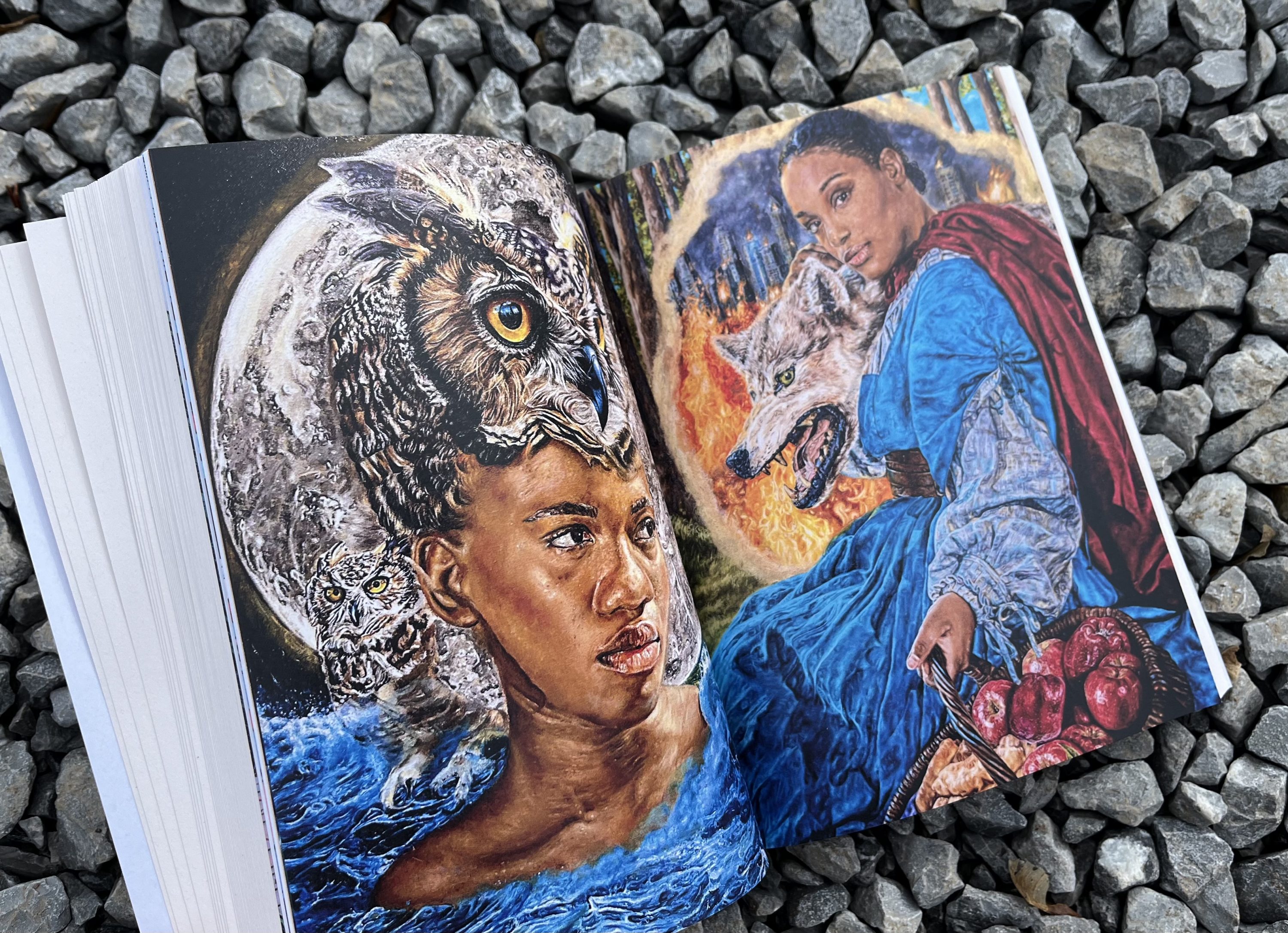

The issue begins with the cover, one of Amuri Morris‘s celebratory oil paintings of Black women, and follows with “Daffodils,” Sonya Schneider‘s poem about the theatrical run of an autobiographical play:

Night after night I watched from the wings

as actors performed the story of my life:

my brother wheeled on in his wheelchair;

my father presented with visions

& pontificating (I used to be a God!);

my mother folding laundry & holding

onto her past; & me, on a tear about fairness

& consequences, practically spitting—

Schneider’s speaker, watching her own childhood recapitualted onstage, is pregnant. Parenting (adoring, inadequate, distressed, or generous) is central to much of the work here: Nate Marshall‘s poems about his baby daughter, Sonia Greenfield‘s “Sundays at Croton Dam,” Lisa Compo‘s “Rain Shadow,” Lois Harrod‘s frank tribute to a mother’s bodily prosperity, and Zack Lam‘s haunted Hong Kong-set “Ash Sestina.”

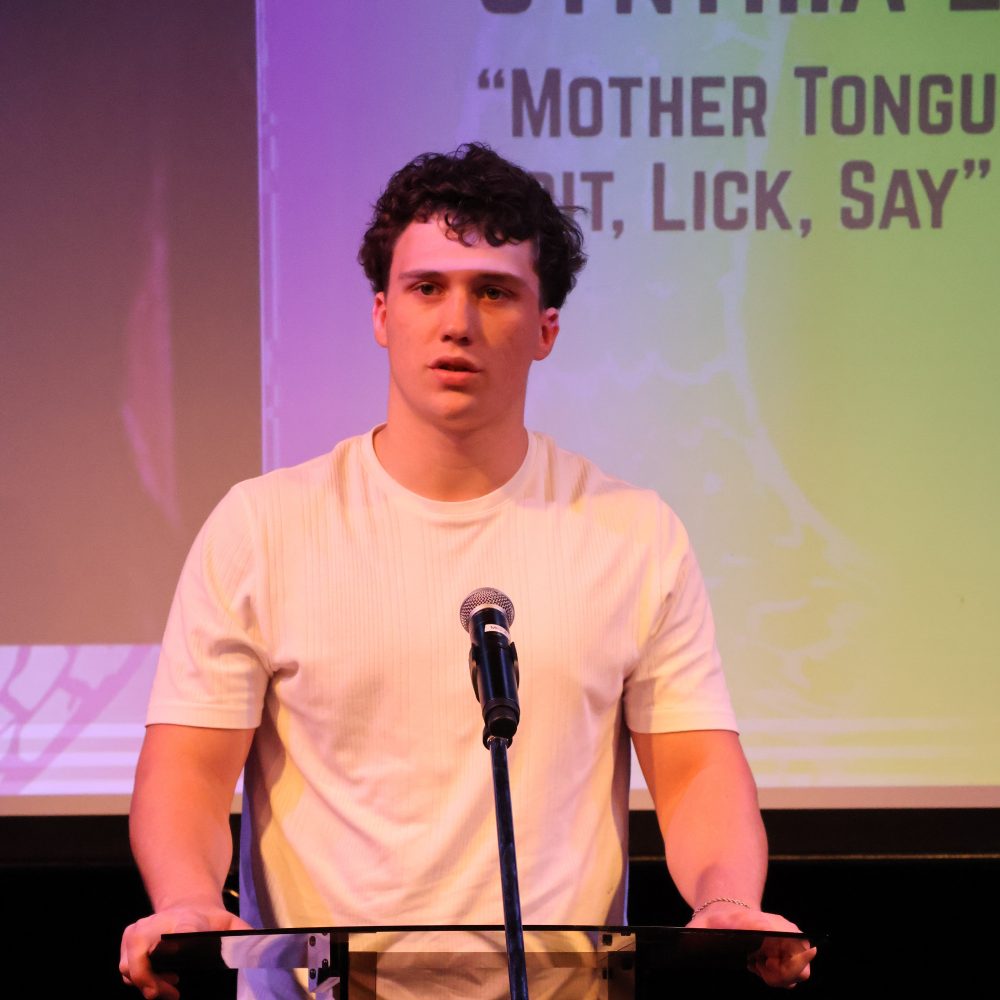

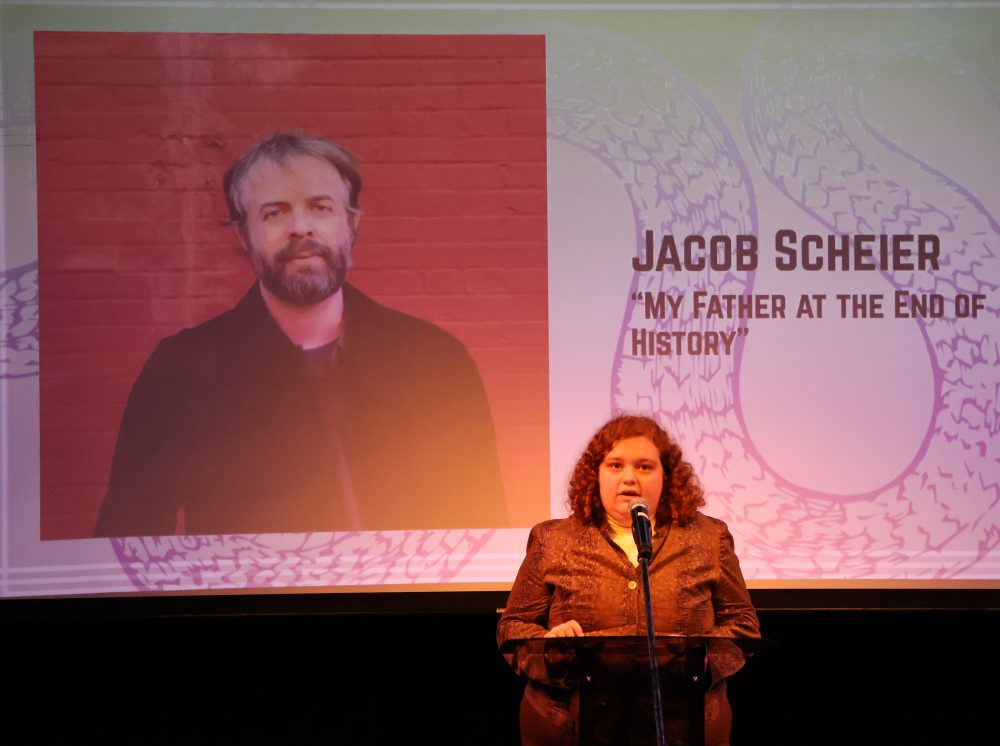

Jacob Scheier‘s “My Father at the End of History,” opens with “For a communist, my father was a competitive man.” and remains relentlessly clear-eyed about that father-son relationship for twelve more pages. Connie Corzilius‘s fiction is helmed by a Cherokee pipeline builder who knows family lore must be more than romance for his granddaughter. Straton Rushing‘s “A**hole, the Dog,” a play about second chances set in an animal shelter, accomplishes an astonishing amount in ten minutes. Cynthia Liu‘s essay on familial multilingualism: “Mother Tongue: Taste, Spit, Lick, Say” describes, in both English and Mandarin, the sense of language loss behind her keen efforts to make her son a fluent speaker of Mandarin:

When thinking about my son attaching himself to my bicep with his nose and mouth, I might think about how a word for kiss 吻 (wěn; to kiss) could also sound similar the word for sniff 聞 (wén; to smell) if you weren’t listening closely. And how another word for kiss (親 qīn; to kiss) is a cousin to but not an exact rhyme for gentle (輕輕地 qīng qīng de; gently) or bruise 青(qīng; green-blue, a bruise). Kiss/gentle might share the same high steady first tone, but kiss ends short on the ‘n’ in the front of the mouth and gentle/bruise ends in ‘ng’ slightly further back of the mouth. All these things flash through my mind as I listen to Mandarin Chinese spoken, especially by native speakers who rattle off conversation quickly; I am a swimmer in strong currents trying not to drown. I’m trying to find my way through the flotsam of my own approximations of meaning. There are too many possibilities, not all of which can be fashioned into a raft.

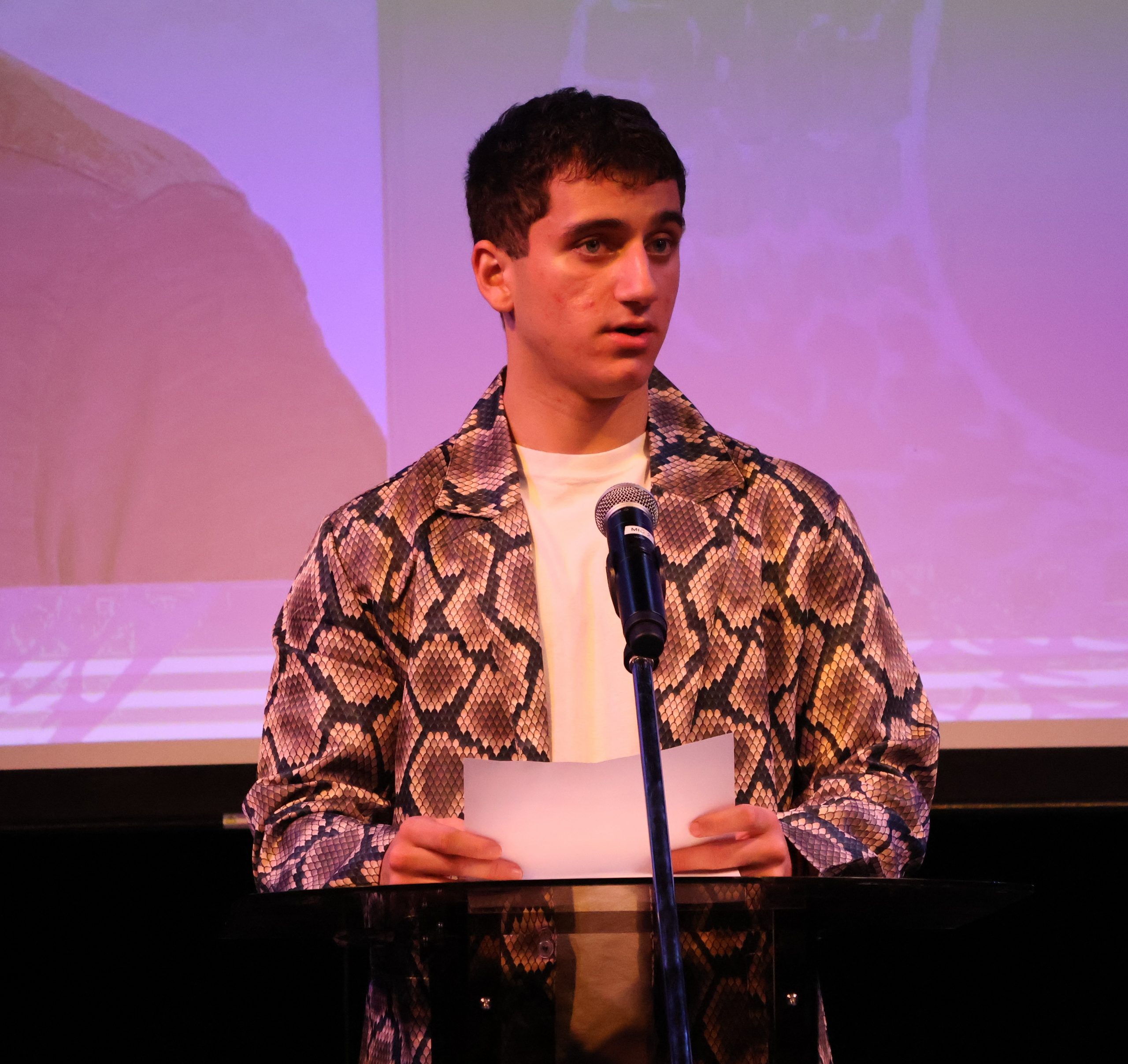

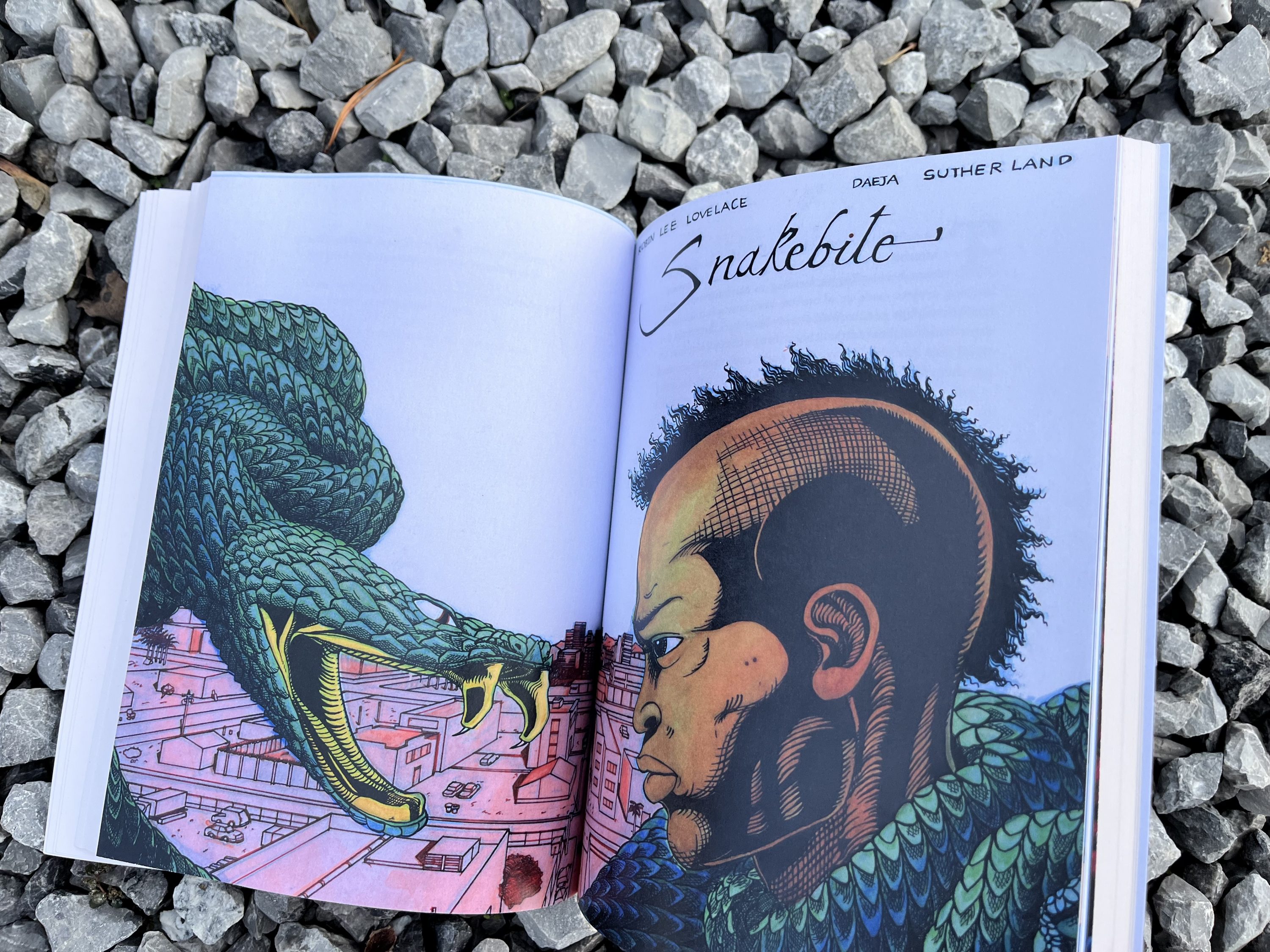

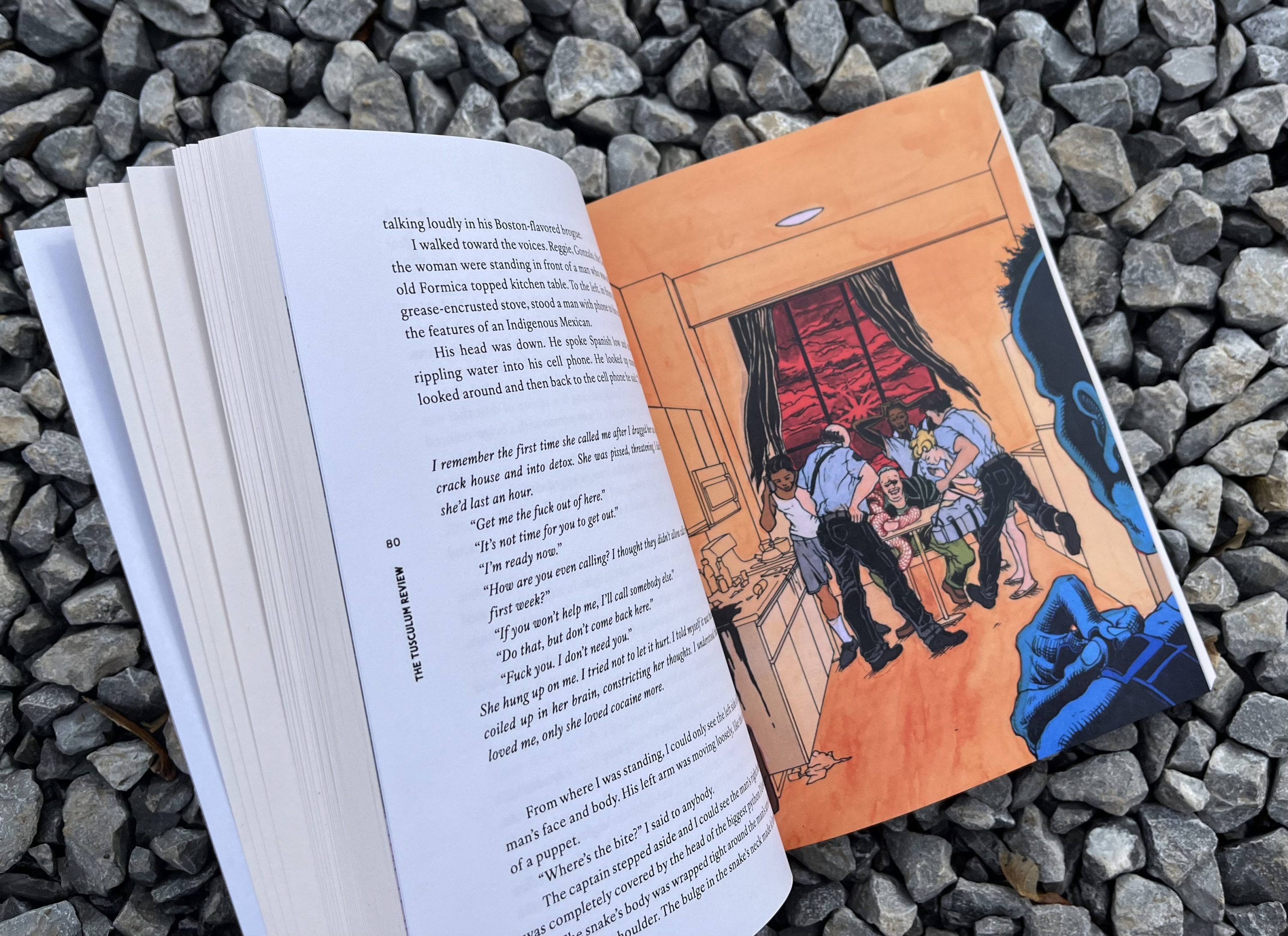

At the center of the volume is “Snakebite,” Robin Lee Lovelace‘s 2025 Tusculum Review Fiction Chapbook Prize-winning story—an EMT faces his biggest fear while grappling with another slippery threat—and comics artist Daeja Sutherland‘s action-packed, human hand-created illustrations of “Snakebite.”

Both Sutherland’s illustrations and Amuri Morris’s painting folio transport us inside fully-realized and emotionally complex experiences. We received dozens of portfolios from artists studying at elite art schools—technically capable, professionally ready, stylishly au courant—but only these two had an artist’s voice and vision: their work is more than mere capable imitation. They recreate human bodies with real weight and palpable energy, draw and paint people ready to crawl off the page. And they do it with their hands, like the masters, not a well-stocked digital toolshed. Remember their names: Amuri Morris and Daeja Sutherland. They’ve only just begun.

The rest of the fiction is luminous, too: G. W. Currier‘s menacing drumbeat of a tale, “Football Lessons for Life at the End of the World,” a retelling of biblical brothers vying for parental approval in a lonely, degraded landscape. Janet Burroway‘s “Basic Training” begins with, “She said, “Don’t hit me!’” and what follows is nail-biting fiction about a suddenly single scholar mother’s cross-continental escape—”She had read her Simone de Beauvoir and her Luce Irigaray; she was a woman who could recognize a red line.”—and stop-start quest for self-sufficiency that includes a cameo by MC Sha-Rock’s early records at a dorm party she attends in a white-knuckle attempt to prove herself to her Black students: “She perceived that Sha-Rock spewed a defiant feminism in a direct line to Kristeva. But she did not say that.”

W. A. Polf‘s “Sweet Love Circles” is a similarly immersive conundrum set in the discord of seventies San Francisco, and “The Encyclopedia of Fanciness” is a new story narrated by a young Gordo that conjures all the raw reality and infectious humor of Jaime Cortez‘s story collection, Gordo. Among the things in Gordo’s “little encyclopedia of fanciness” of 1978 is “PRIVATE BEDROOM: I seen this a million times on TV, and it is definitely fancy to have a bad day at school, jump into bed on your belly without even taking off your shoes, and cry, cry, cry on your pillow because it’s not fair.” Also “GLASSES: Somebody in the family wearing glasses to work is 95% fancy.”

The issue stars Ethel Morgan Smith‘s ever-relevant essay “Love Means Nothing,” about sport devotion, middle-aged vocation, and the deep disappointment of bald racism, reprinted here from our third issue (2007) with an urgent afterword. Like Claudia Rankine in Citizen: An American Lyric (2014), Smith grapples with microagressions against Venus and Serena Williams:

Cliff Drysdale endeared me once by using a phrase I hadn’t heard since my grandmother was alive. Not that he’s old enough to be my grandfather, or father for that matter. He was speaking about a tennis match between Pete Sampras and someone, and he said, “When Sampras gets a lead ‘that’s all she wrote’.” So imagine my surprise when he spoke and still speaks of the Williams sisters having a “strange upbringing.” They were poor. Not strange. Or when one of the sisters is down in a match, his way of saying, “She will now self-destruct.” He even described Venus`s body as giraffe-like. What was happening to my world of tennis? When Mr. Drysdale talked about Agassi, Sampras, Roddick, or Federer, his voice changed, his energy was higher, he even laughed. I want Mr. Drysdale, the gentleman of my past, back.

The poems here are all stylistically surprising and wide-ranging in subject: Alexander Lee‘s “Memorial Day & How We Fight” captures the physical and emotional cadence of adolescent fraternal squabbling; ellis jake solie‘s “Adequate Intake” is a formally-inventive meditation on the amounts our bodies need and the things they want; Jeffrey MacLachlan‘s deliberate and frenzied war poem “Friendlies Will Be Marked” is written in directives to a powerless “boy.”

Also not be missed are confidence-sharing poems: Ace Boggess‘s “Expert at Crushing Pills and Carving Their Powder into Lines, I Called It Art and Wanted the World to See,” Ken Holland‘s “Not Fibonacci,” and Laney Nielson‘s “Hydrangeas.” Mac Gay‘s “Asphalt Jungle” begins like a meditation on a dog-eat-dog world—”For most in the wild, everyday / is the war in Ukraine”—but turns into something more.

This volume is too pressing and dense with beauty to summarize. Our student editors marveled at this work, studied and discussed it closely, celebrated the authors at our live launch, and profiled some of the authors and artists in pieces that will be published on this website in January. Reading literature with students is one of the surest ways to appreciate it more, and these profiles will likely give Tusculum Review readers some of that pleasure.