The vicennial volume of The Tusculum Review considers everything most on the world’s mind right now: testosterone, pregnancy, fertility, childbirth, warfare, male desire, female diplomacy, immigrants and indigenous, nonbinary bodies and written forms, addiction, religion, God, disconnection/solidarity, warrior PTSD, age/youth, goodness/guilt, grief, and land.

The issue opens with a doctor whispering to a grandmother on the floor in poet Tess Congo’s “A Performance for Future,” and poems by Summer Barnett, James Braun, Mike Good, Brian Patrick Heston, and Melissa McKinstry plumb maternal and paternal ancestral legacies.

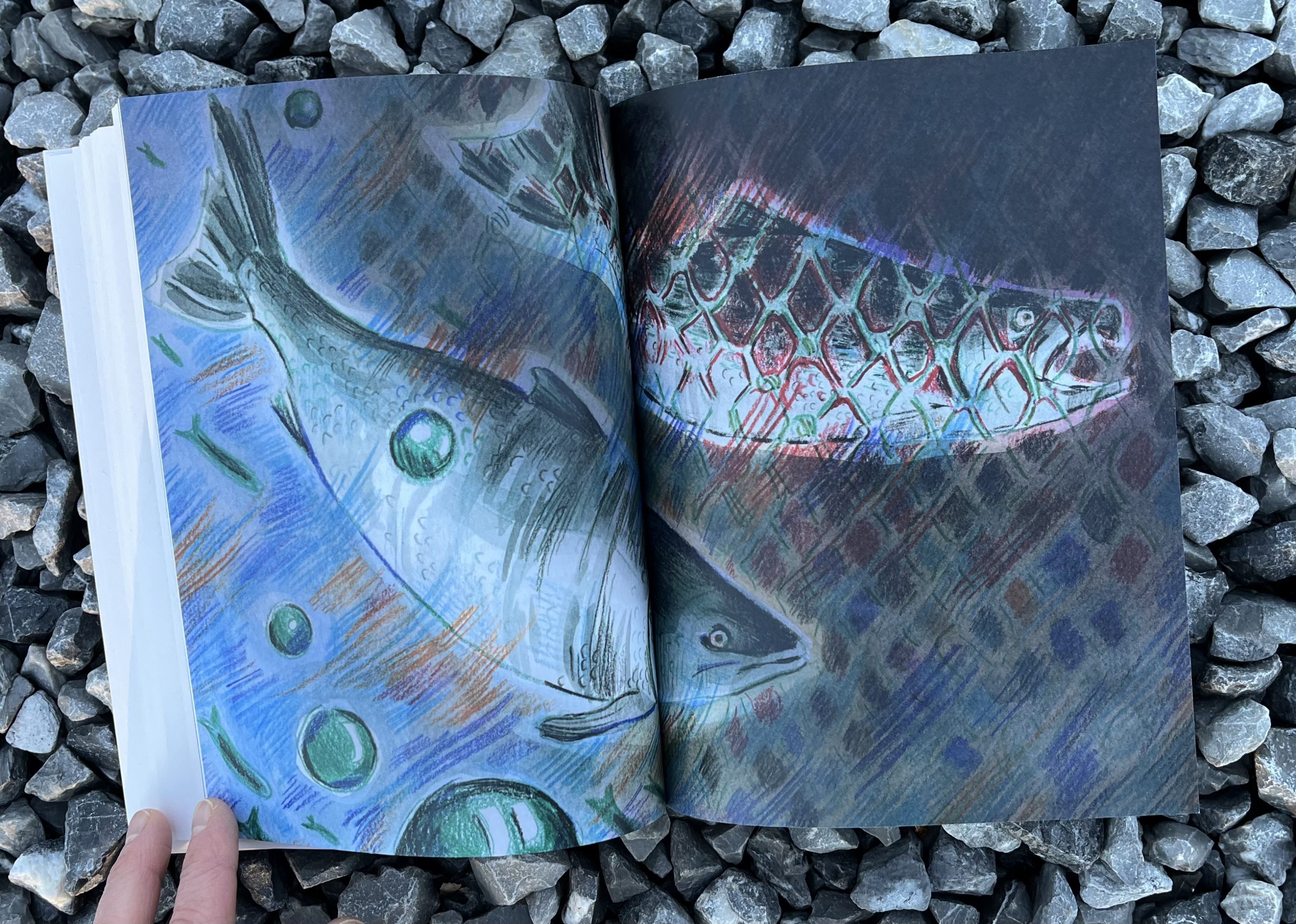

Essayist Mirela Musić joins a salmon-fishing operation in Alaska and contemplates her Montenegrin parents’ Brooklyn marriage and the boat captain’s escalating insinuations. Guest judge Mary Cappello chose “The Nature of Alaska” as the winner of the 2024 Tusculum Review Nonfiction Chapbook Prize: “This is an essay about the precariousness of sleep; the indefinable nature of home; and the power of place to hold us or eject us. It’s about finding family or fleeing family; it’s a wrangling with the terms by which we accept our own oppression.”

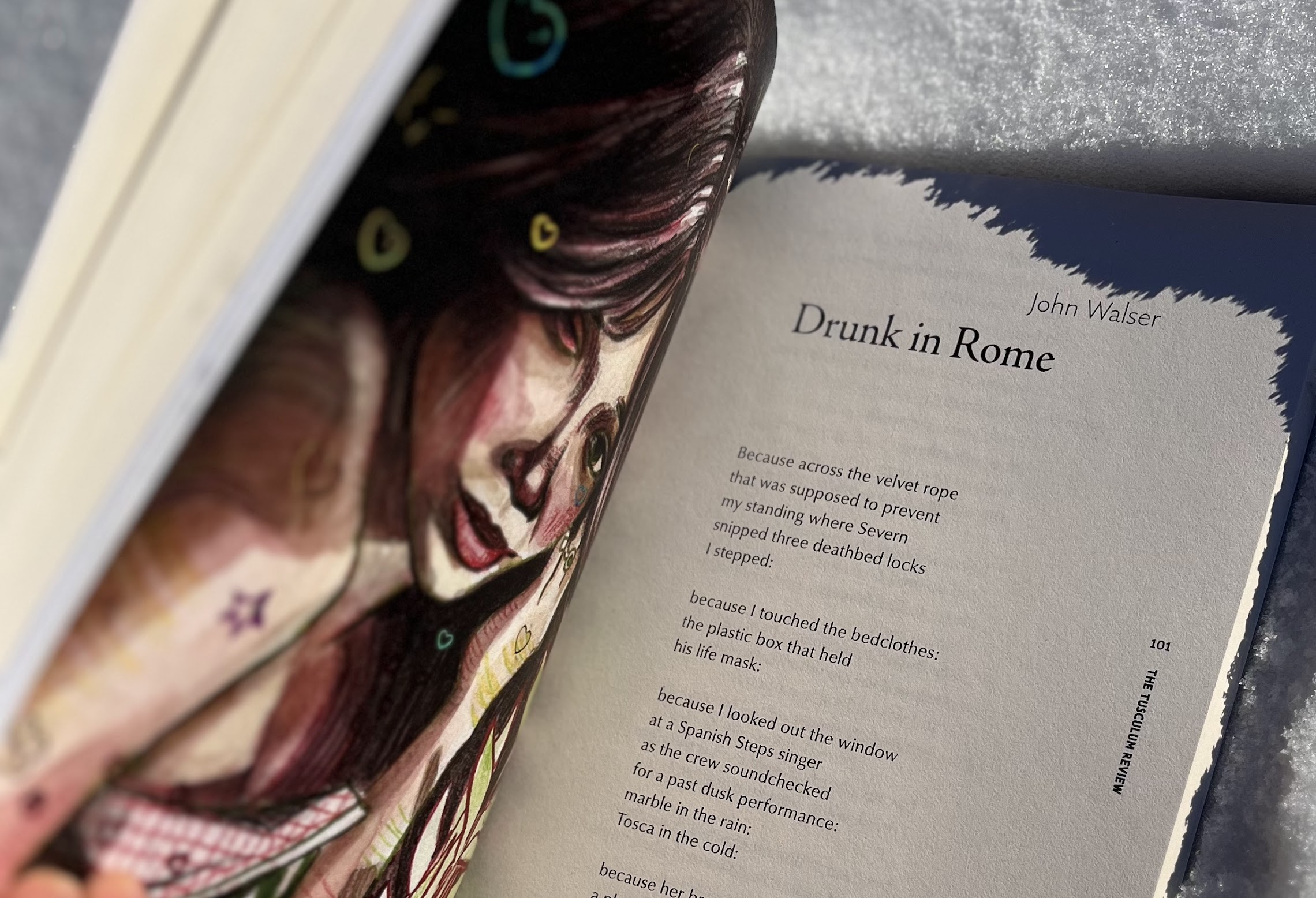

Musić’s essay is at the center of the volume with ocean-immersive, tension- and color-filled illustrations by Virginia Commonwealth University BFA candidate Ayla Bramblett that are as sharp-toothed as Musić’s essay. “The Nature of Alaska,” published in the journal in its entirety, is also available as a stand-alone limited edition chapbook. Similarly not to be missed is a folio of Bramblett’s self-portraits and a description of her artistic concerns and craft methods.

Glenn Shaheen’s inventively structured essay, “Kneeling Before God, Man, Self” inventories guilts and pleasures past. Garry Cooper’s “Lighthouse Tender” chronicles the hopeful admiring of passers-by and yearning for connection. Orchid Tierney’s “the hysterical essay: poetry and the breakdown of form” blasts the conventions of academic composition. Rachel Becker’s “The day after the last school shooting” makes an exhausting list of all the things the speaker might need to do to save children next time.

Childcaring and -bearing are central to many of the essays and poems here: Makayla Gay’s “Excerpt from 300-Question Personality Test to Give to Potential Egg Donors to see if They Have the Right Kind of Personality to be passed on to other People’s Children;” Jessica Mohsen-Crellin’s “A Brief Experience with Infertility as Told by My Mother, Laughing;” and Suzanne Manizza Roszak’s sharp “Birth Rehearsals,” in which she juggles her second pregnancy, workplace misogyny, and dismissive medical care. The pregnant speaker of Rachel Marie Patterson’s “Capital Health” attends her partner in the ICU.

Sheryl Boris-Schacter’s “The Dinner Table” tracks her child’s evolving gender expression and Dalanie Beach’s “Unreadable: The Complexity of Nonbinary Embodiment” traces the way their own is perceived:

At the vet’s office, where I drop off my cat for bloodwork a few hours later, the lady at the desk refers to me with feminine pronouns when she speaks to her colleague. I deflate. When I turn to go, she picks up my cat in her carrier and says in a high-pitched voice meant to speak for the animal: “Bye, Mom!”

I tell myself it’s fine, I sort of am Biscuit’s mom (what else would I be? Her uncle?) and hurry out the door. As I’m walking to my car, a line from Paul Preciado’s book, Testo Junkie, pops into my head: “femininity sticks to me like a greasy hand.”

Geoff Wyss’s riveting, candid, and textually acrobatic “Victoria Miranda” examines the ways men see and construct women in life, porn, and other narratives:

I was looking at women with a need I could not define well before I ever saw pornography, before I knew what sex was, watching them with the kind of closeness that makes nonsense of the difference between perversion and reverence. Other boys were givens, like roads and houses necessary and factual, but girls held the hope that life might contain more than the mere living of it, a promise that something finer and brighter existed than the unreconstructed world. In first grade, I was caught trying to look through a bathroom door vent to see Lesley Fletcher naked . . .

He considers the women in his autofiction and his life, the male characters he’s created who are bound by their desire for women. He contemplates, not unseriously, the effects of testosterone on the world and how voluntary chemical castration might stabilize the personal sphere and the globe while neutering the desire at the core of all narratives. You haven’t read anything like this essay, with its braided subjects and frank revelation of the author’s interior life. It’s a literary and sociological achievement that ends, unexpectedly, with a reference to Martin R. Delaney, Frederick Douglass’s co-editor of the abolitionist newspaper the North Star.

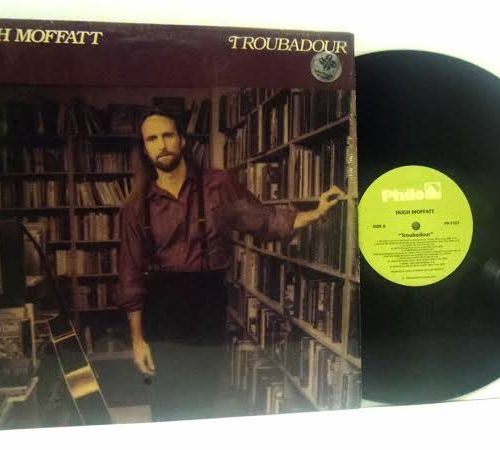

Poet Tyler Lemley writes about desire and being desired in “I’ve Always Had a Thing for Older Men.” Musician and dramatist Hugh Moffatt’s play “A Park Bench (Chapter 1—The Alien)” considers the challenges and insights of communication across a six-decade age gap and different planetary origins.

Karen Fisher’s “The Bright Suns and the Dark Suns,” an excerpt from her next novel, follows young Civil War veteran and doctor Briggs into the crowded post-war frontier after he finds himself unable to live in New York City with his wife. He walks into the west, through varied landscapes described with the same outdoor acumen and poetry that made the prequel to this book, A Sudden Country, an award-winning favorite: “Alone, he finds his way to brinks and descends. Swamps or thickets he doesn’t care, or direction, generally west. He is looking not for a particular place but for a simple end to feeling.”

With his uncle Sewell’s team, Briggs cuts a trail through to Yellowstone, then joins the Hayden survey:

He works until full dark, then sets down his pen, pockets the book, rises and walks by the swinging light of the lantern through the trees and into the meadow. A deer breaks and bounds.

Have you heard that it was good to gain the day?

I also say it is good to fall, battles are lost in the same spirit

in which they are won. I beat and pound for the dead . . .

For a moment he stands beside the compass just looking up at the sky, the still and uncountable stars, and Whitman’s lines come to him, they have memorized him, lodged in him, like songs, like psalms, without his even trying.

Fisher’s historical fiction is about the war-wounded, the partitioning of land, and attitudes toward the indigenous (“He passes among natives known only by savage report and they do him no harm.): themes at the center of all human tales from before Homer’s Odyssey to present-day narratives of homeland loss and shell shock.

Interspliced with Briggs’s journey is the mournful voice of Weletsese, a Nez Perce woman who’s lost her husband and daughter Meywinme to the marauding bands of men tacitly deputized by the government and rumor to “kill any kind of Indian not on a reservation.” Before Briggs meets Mrs. McWilliams, a wealthy woman who’s hidden away Weletsese and asks him to set her broken limb, Weletsese remembers the men assaulting her after they killed her husband:

. . . she bucked and fought but hard metal pressed above her ear . . .

we humans together are not tamed not afraid to be killed but

she alone . . .

in one story she kills them

in one story she calls on hornets who arrive she sees their horses run bucking

through trees everything scatters they get impaled on trees

Like Briggs and Weletsese, the speaker of Charles Kell’s poem “Atheist in AA” considers stories, truth, God, art, one’s fellows, and the utility of those things to pull you from the brink. In his beautifully formed “Fortnite with Squirrels,” Dustin King muses on these foundational philosophies, too. London lay community worker and warden for St. Mary’s Battersea Evalyn Lee’s poem “Because Writing Hurts Too Much” is a thick-aired fireside tending to a dying 58-year-old. Gregory Emilio’s “Regarding the Wine-Dark Sea” begins with Homer and “bottomless resort drinks,” puts its swimmers through a death-close spin cycle, and ends “shaking like a grunion.”

John Nieves’ “Ending in Apostrophe (Don’t Contract, Don’t Possess)” asks: “How/do I make my tongue and my lips do anything/anyone can understand?” In the volume’s final poem, “Cento for the Hungry,” Anna Sandy Elrod uses the words of 17 poets–Homer, Ross Gay, Dorriane Laux, and Ocean Vuong among them–to say it best.

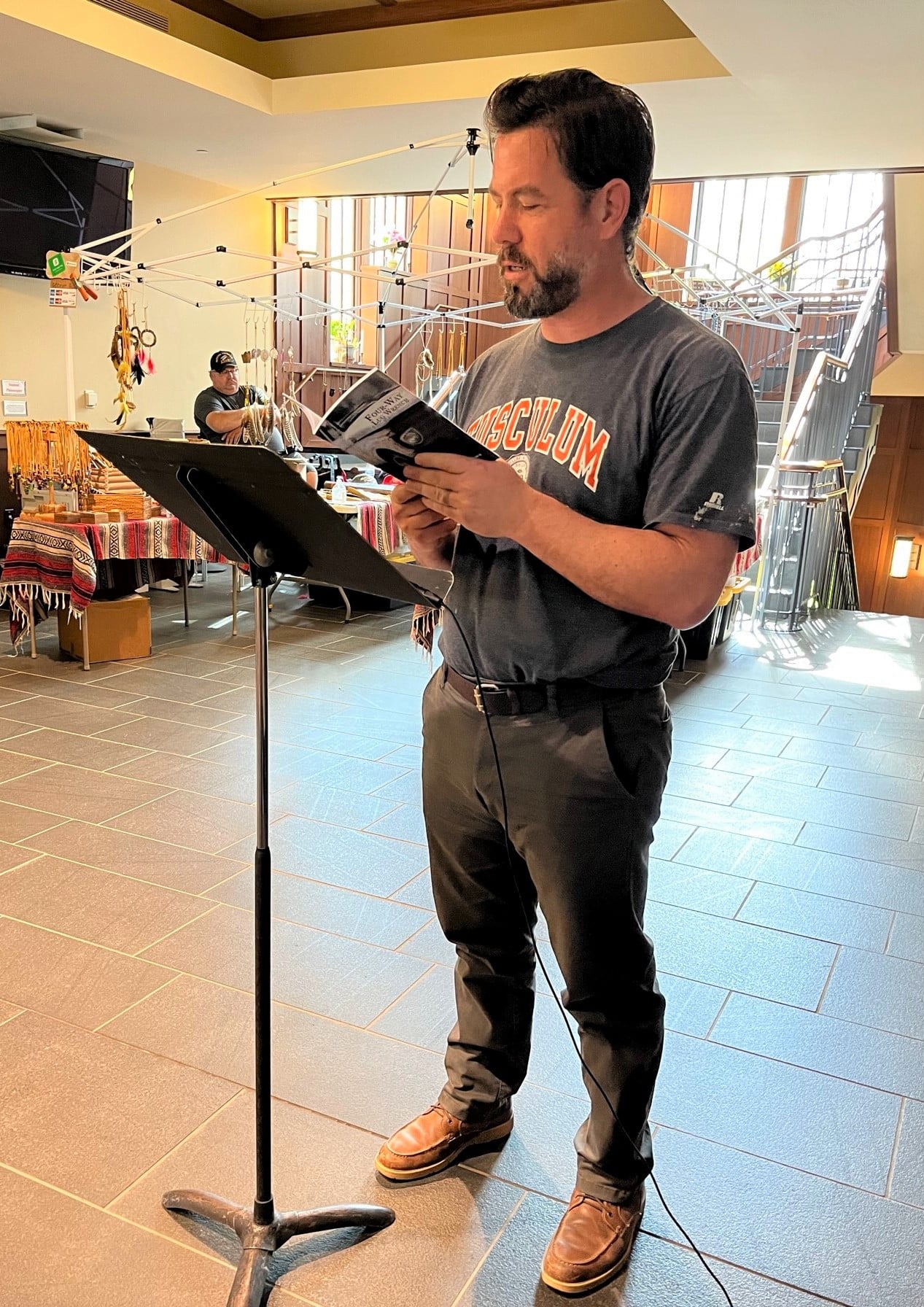

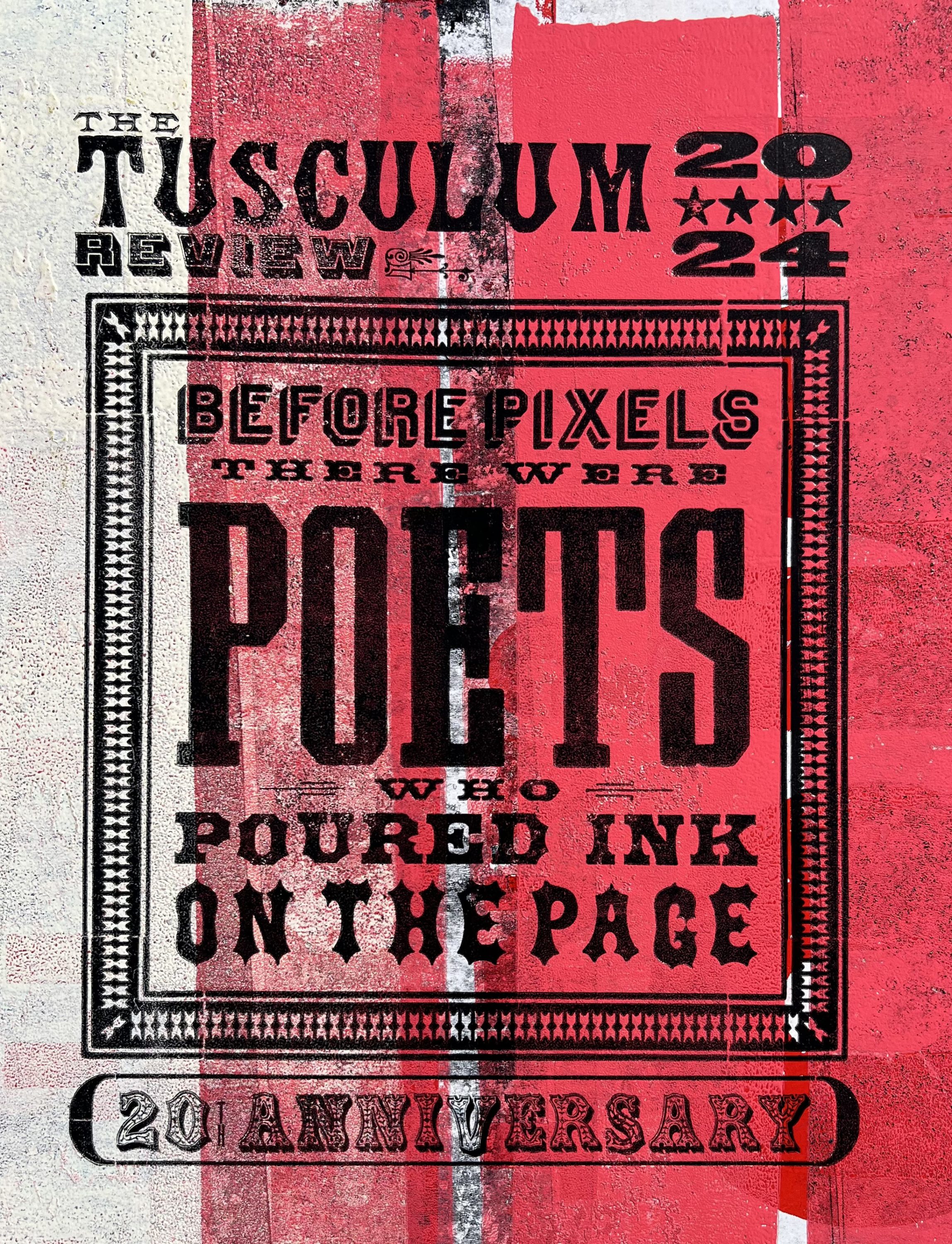

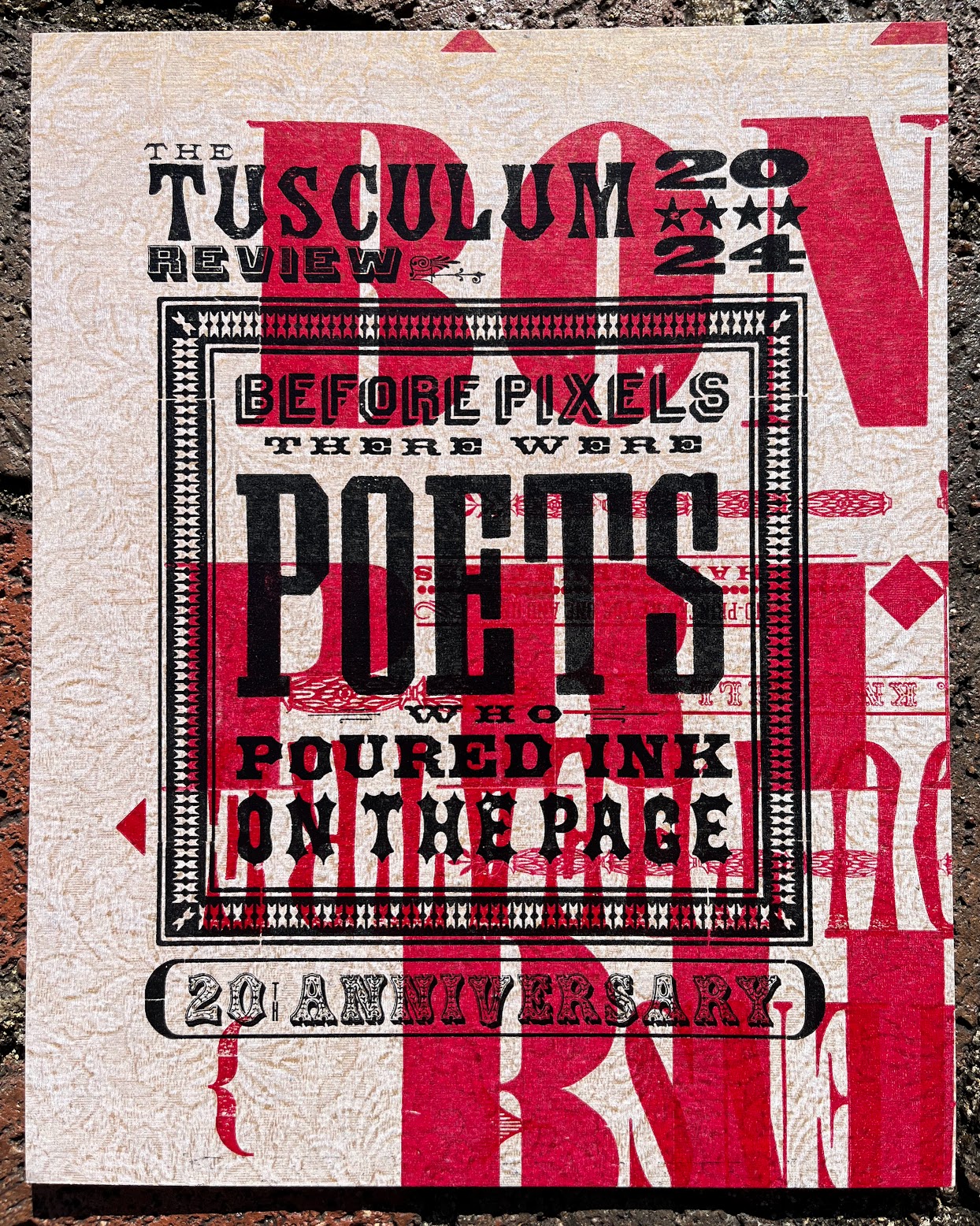

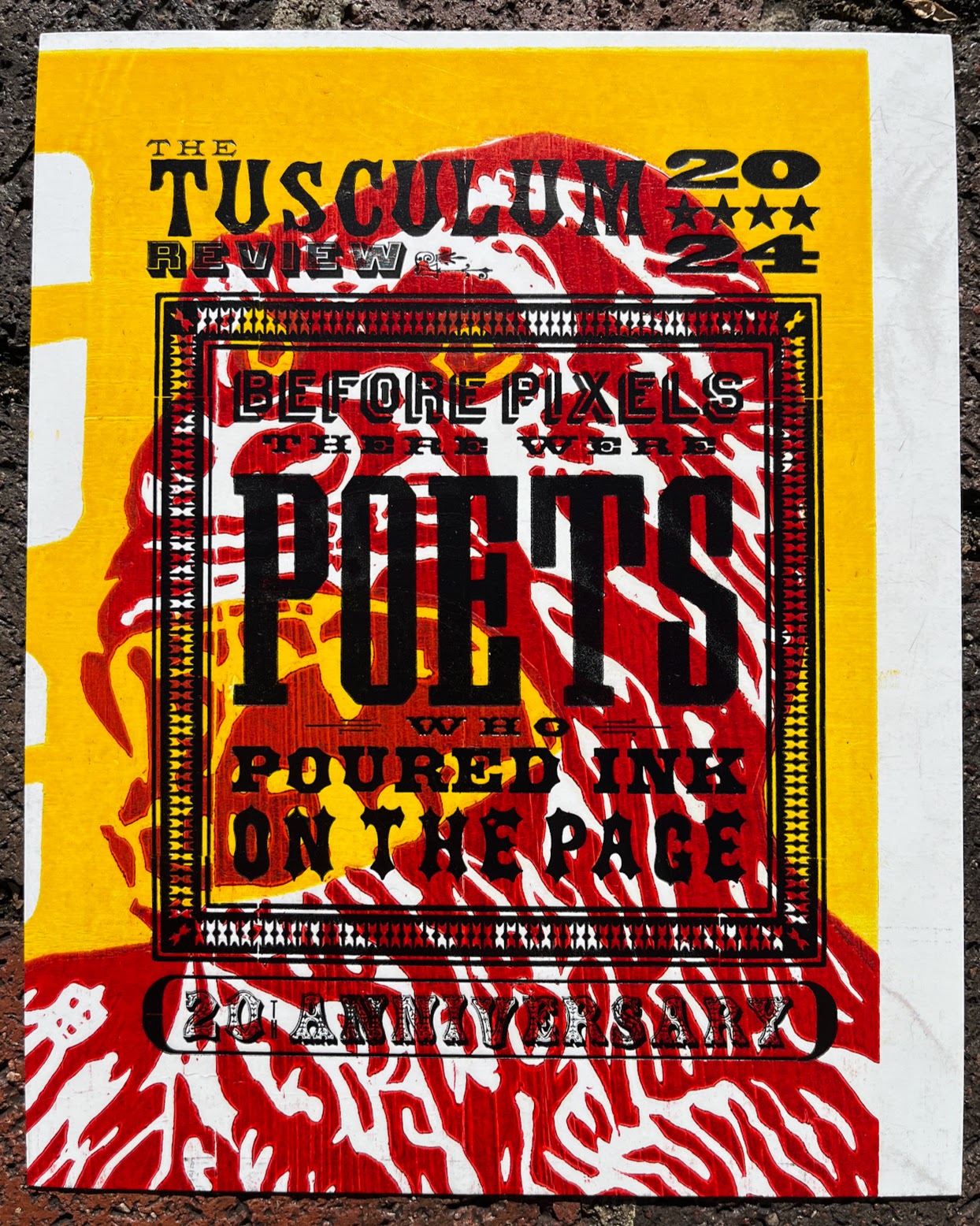

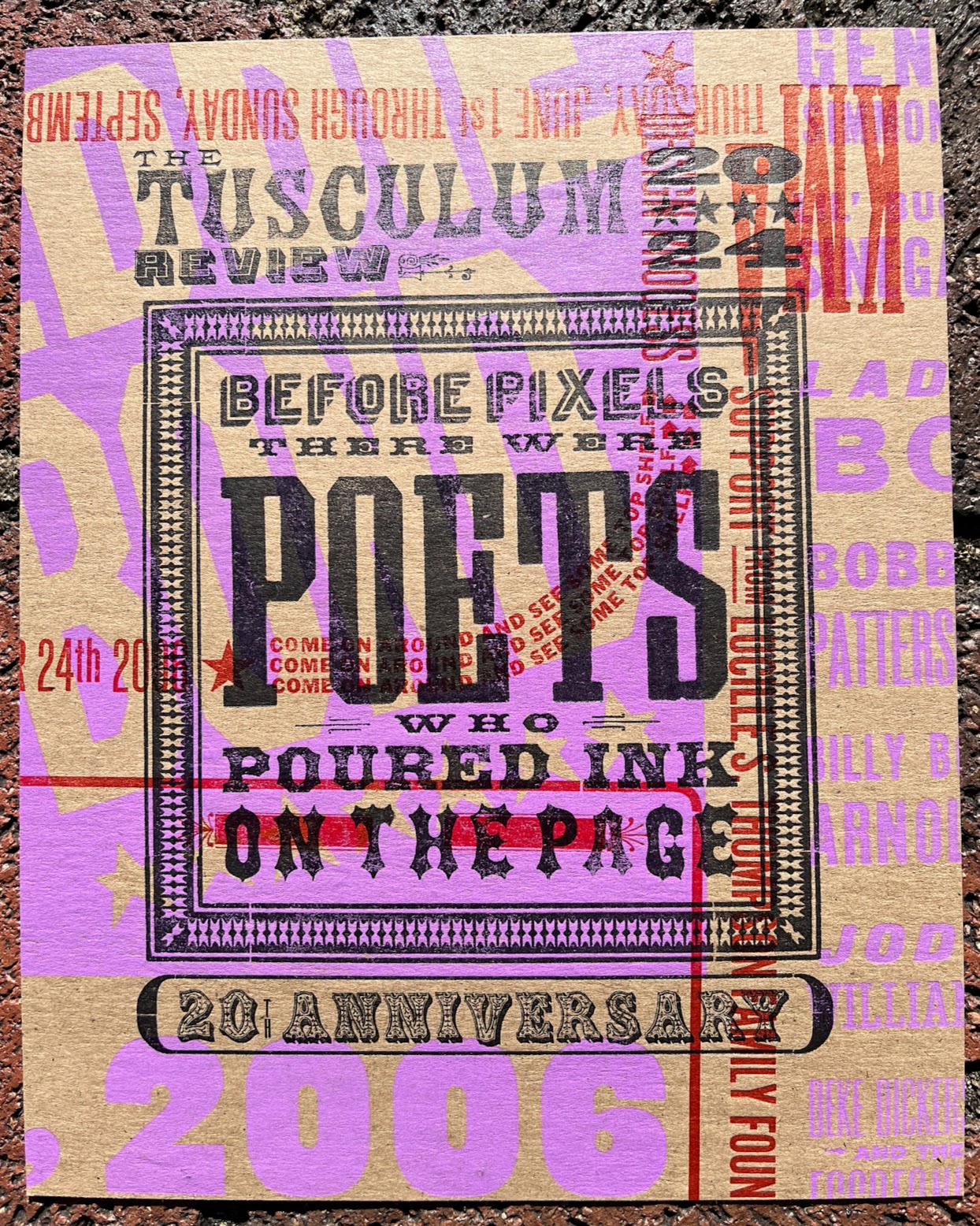

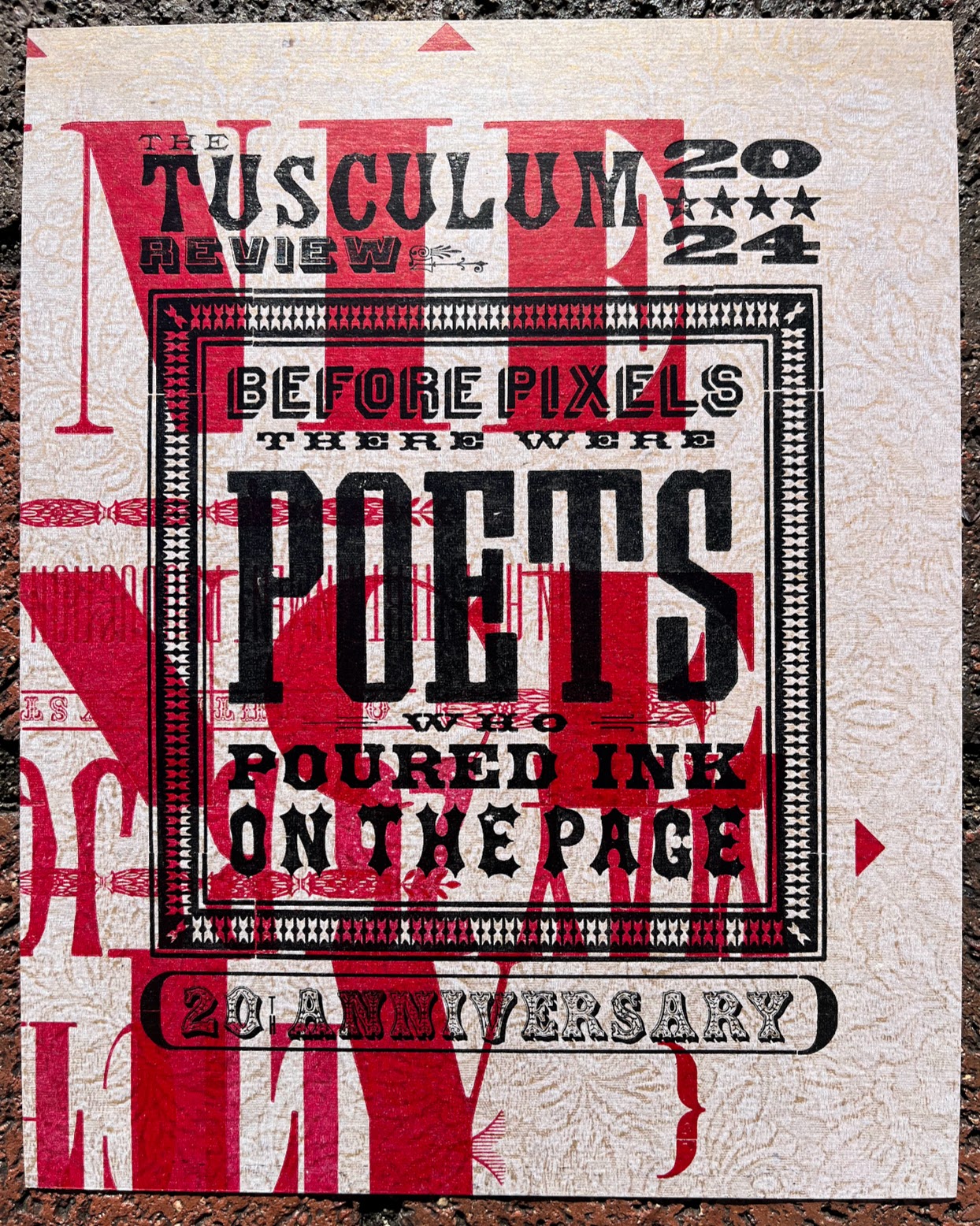

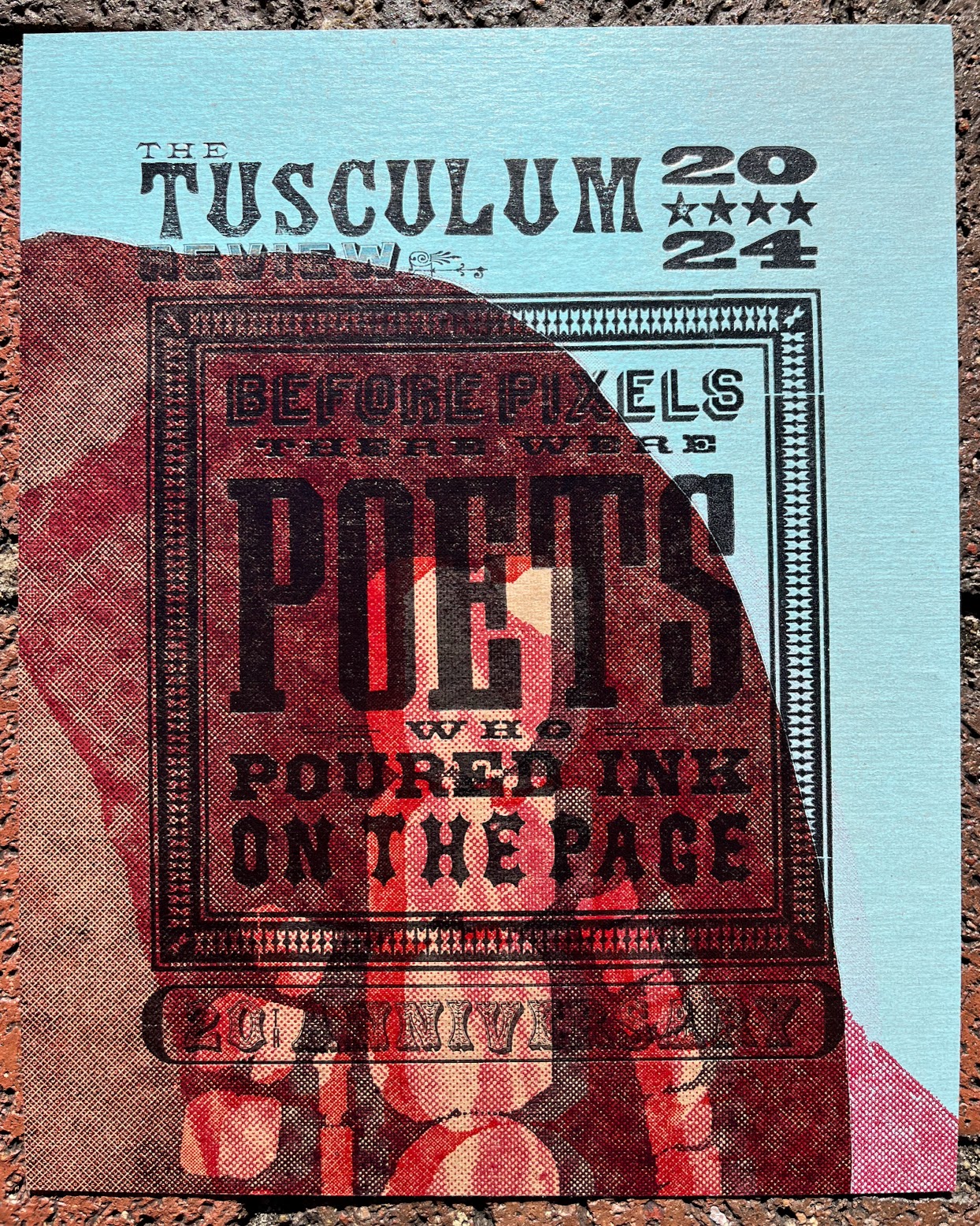

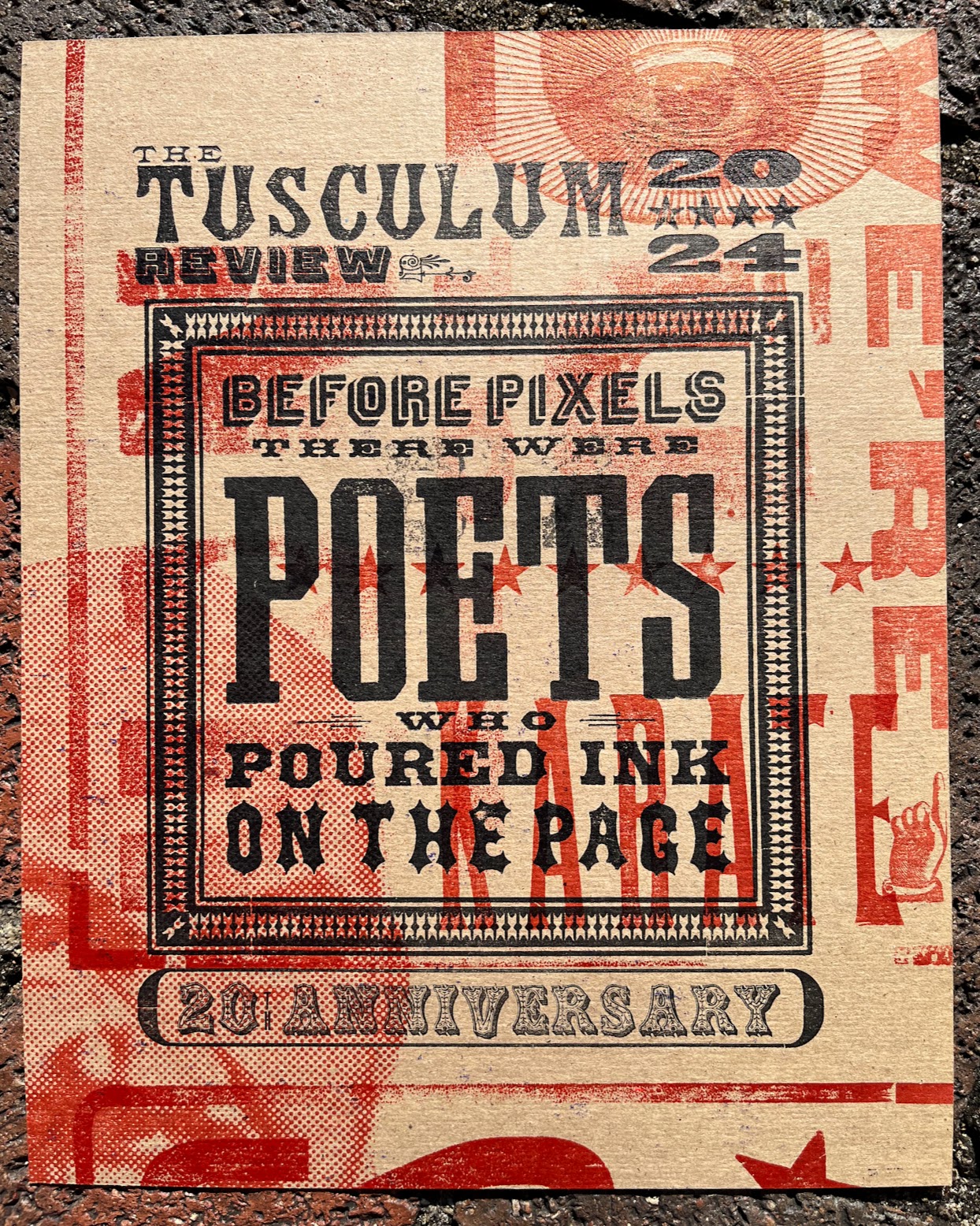

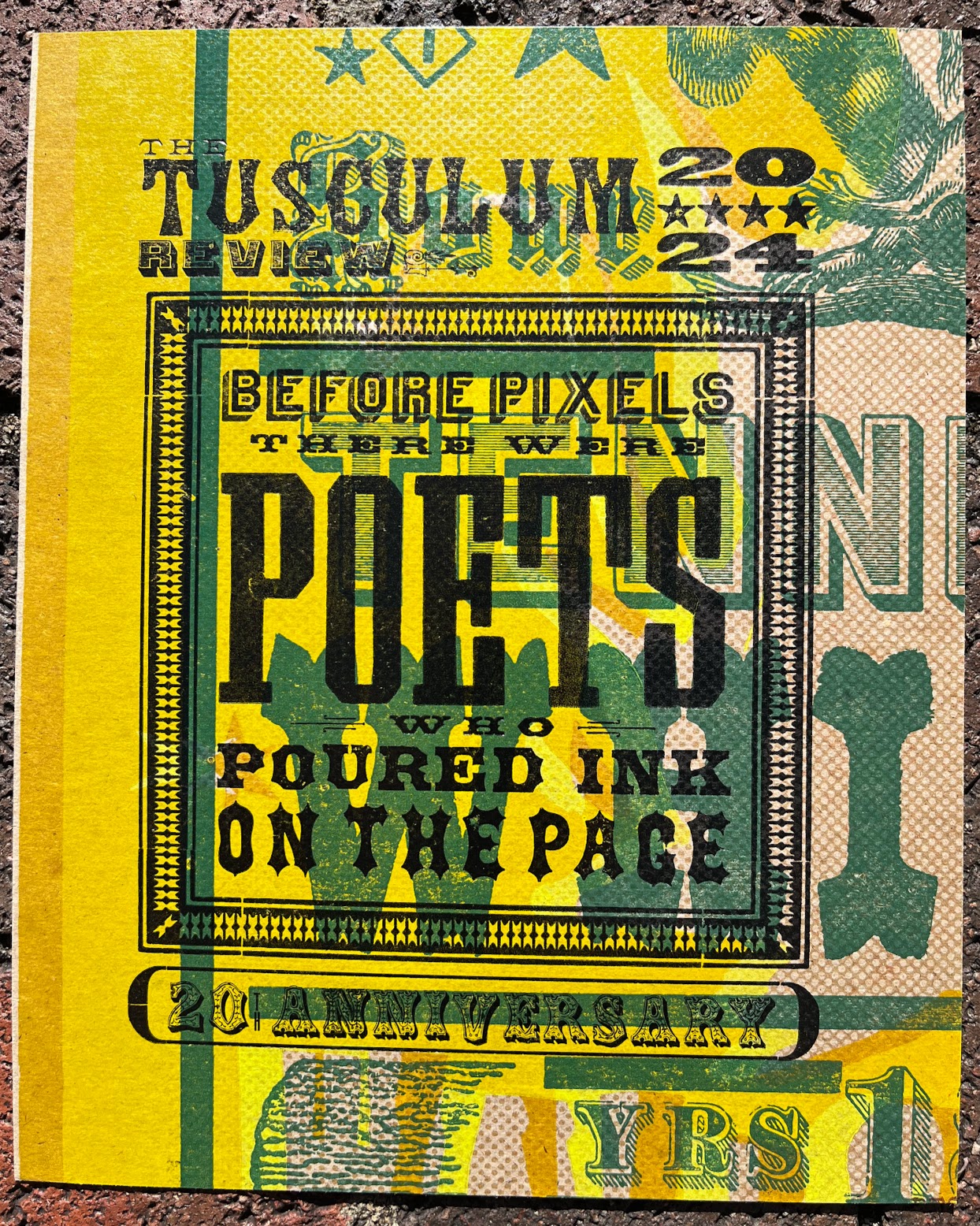

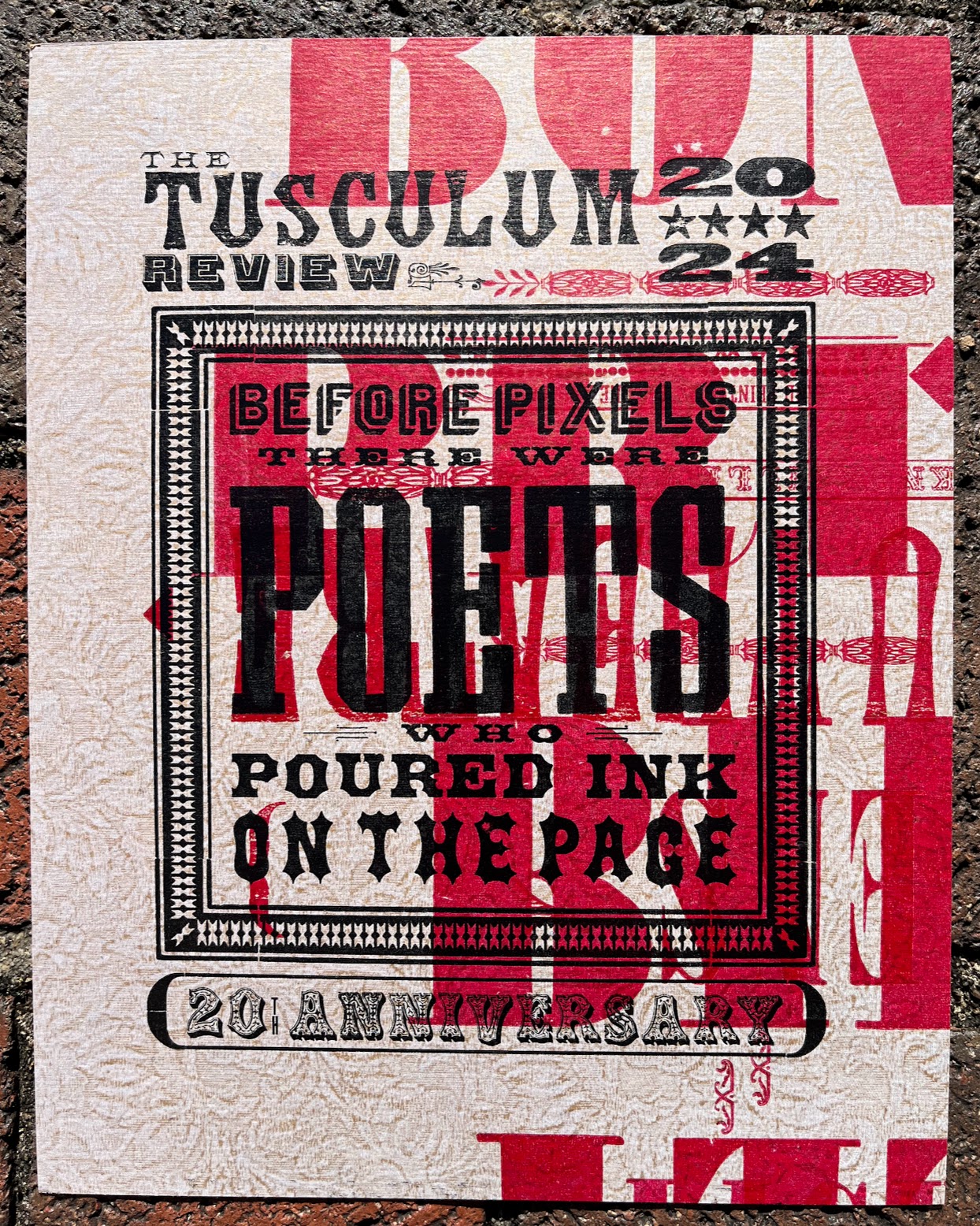

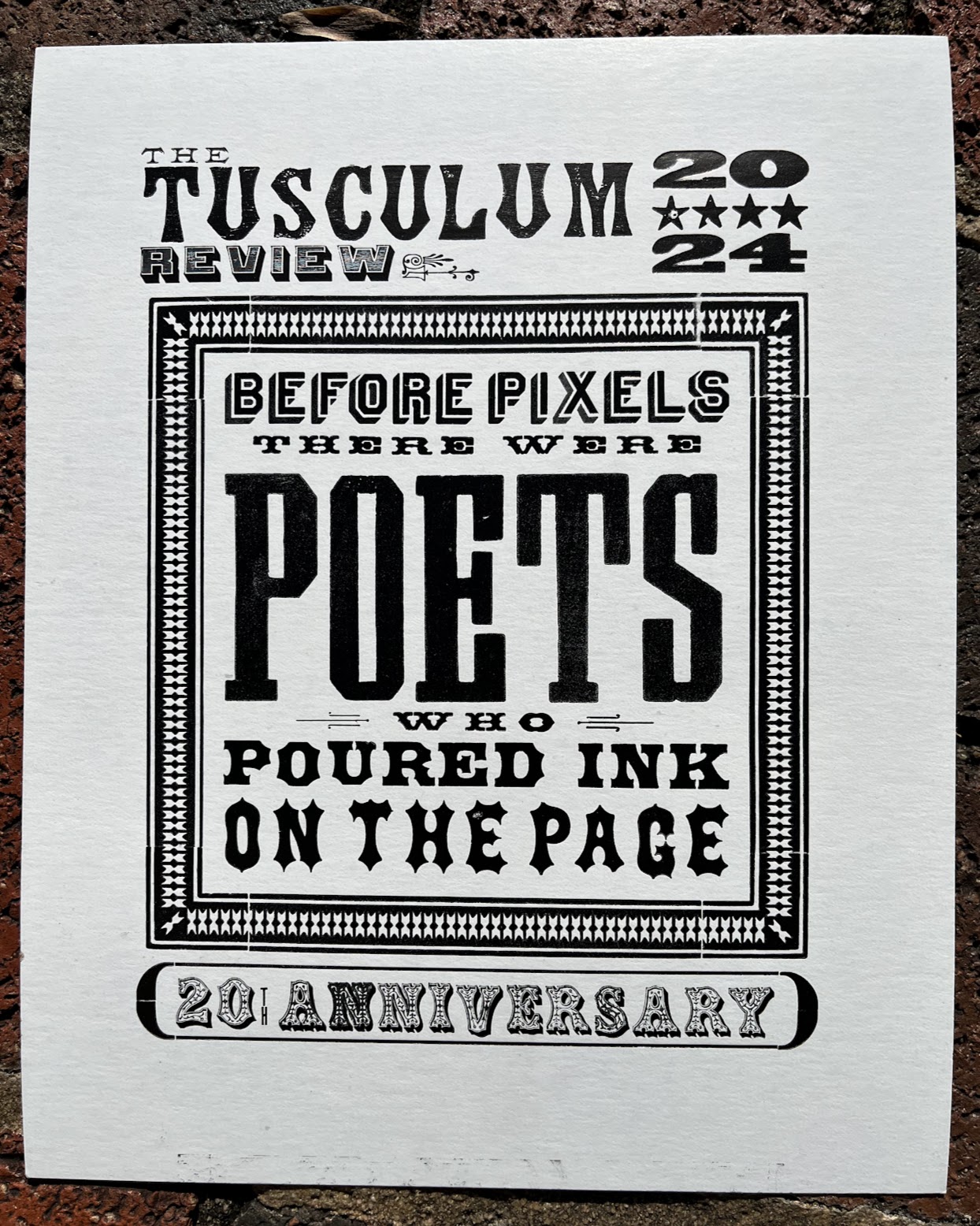

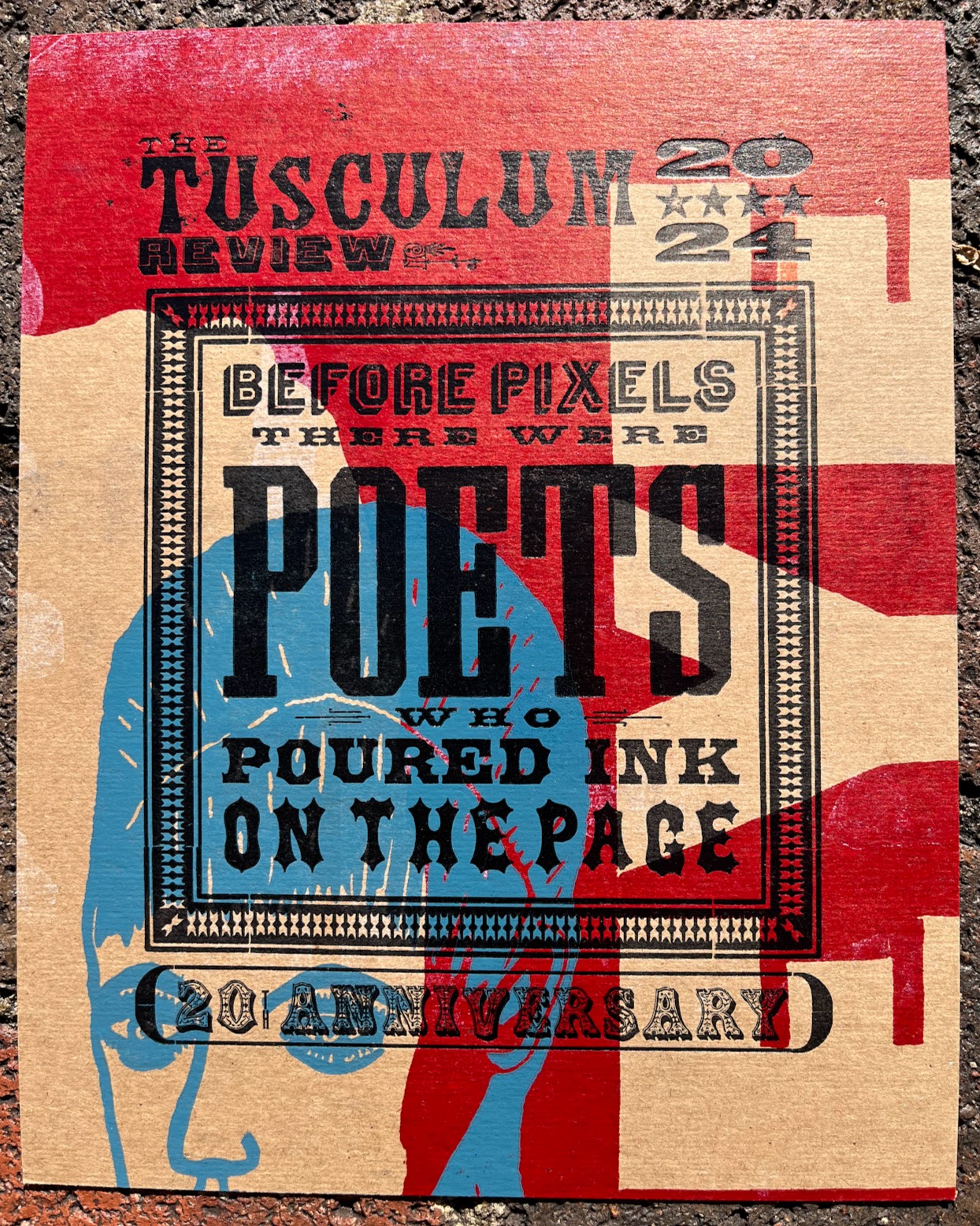

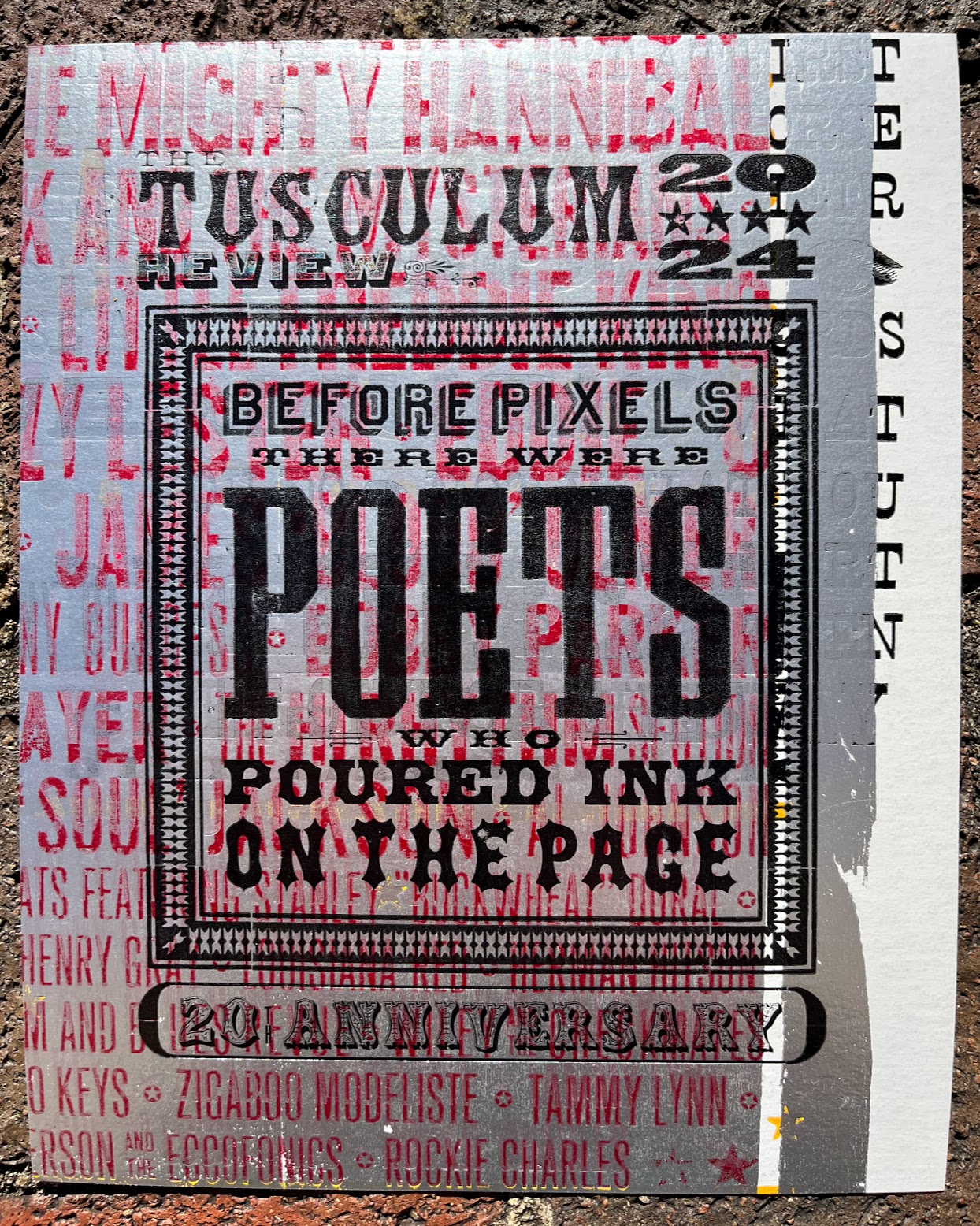

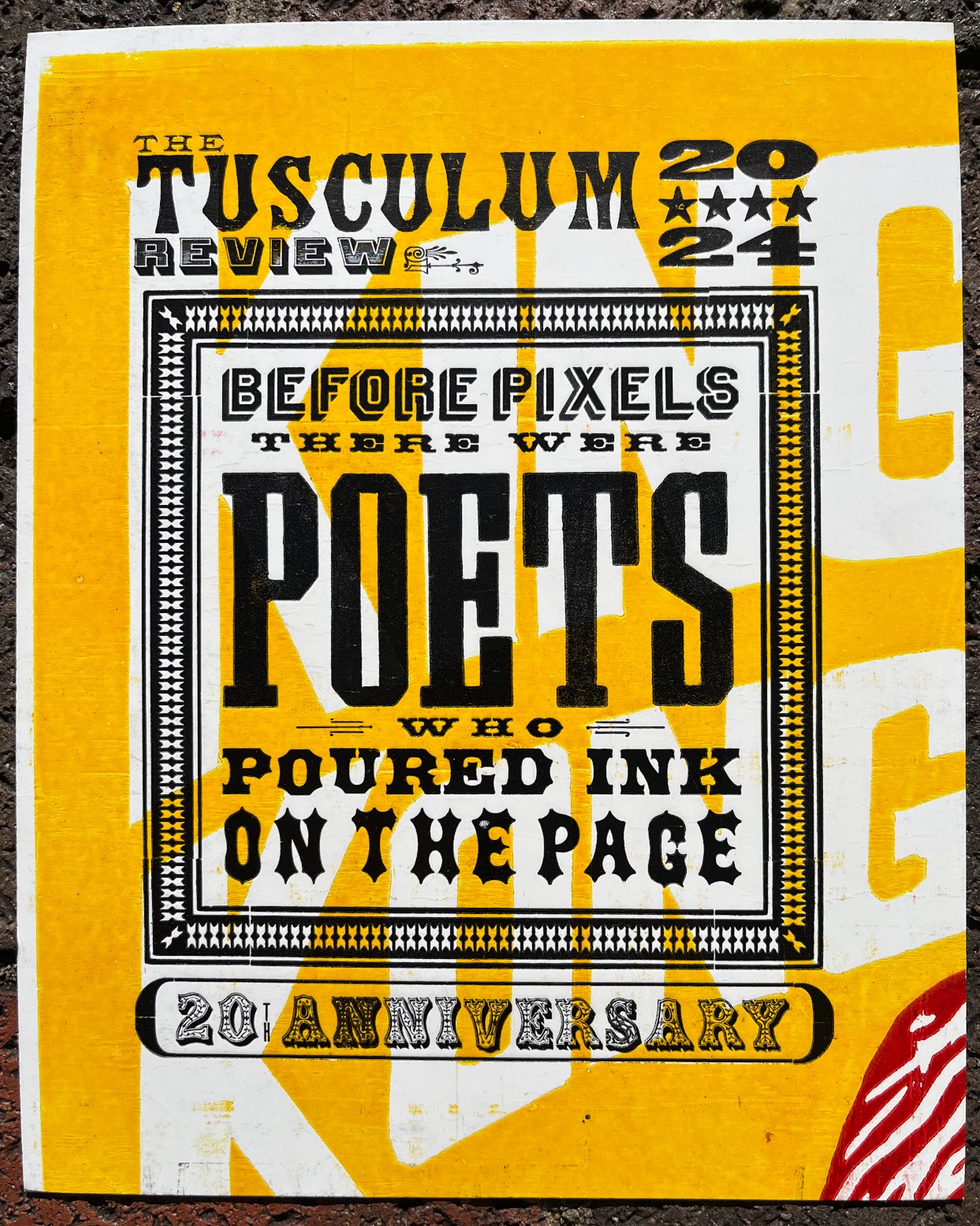

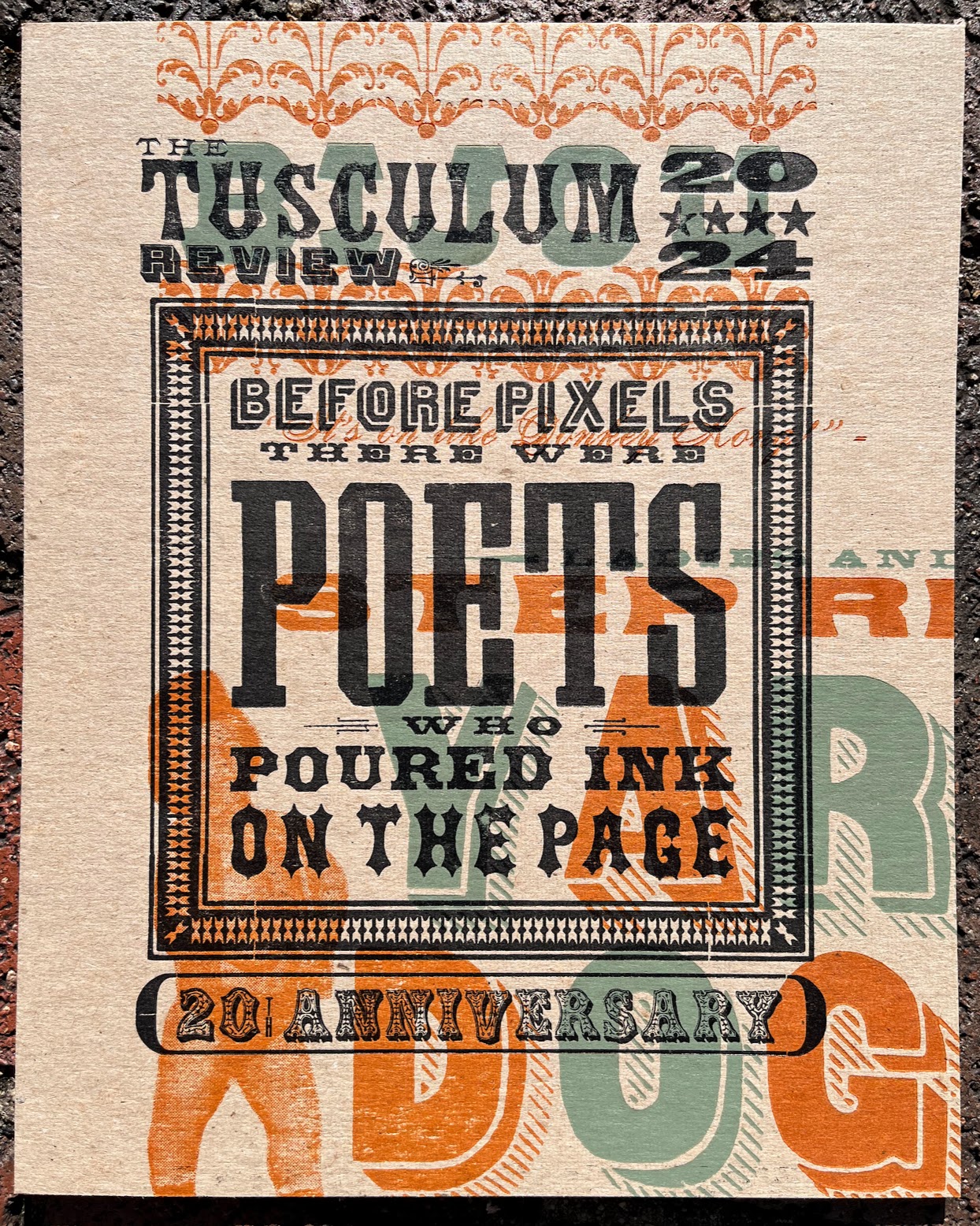

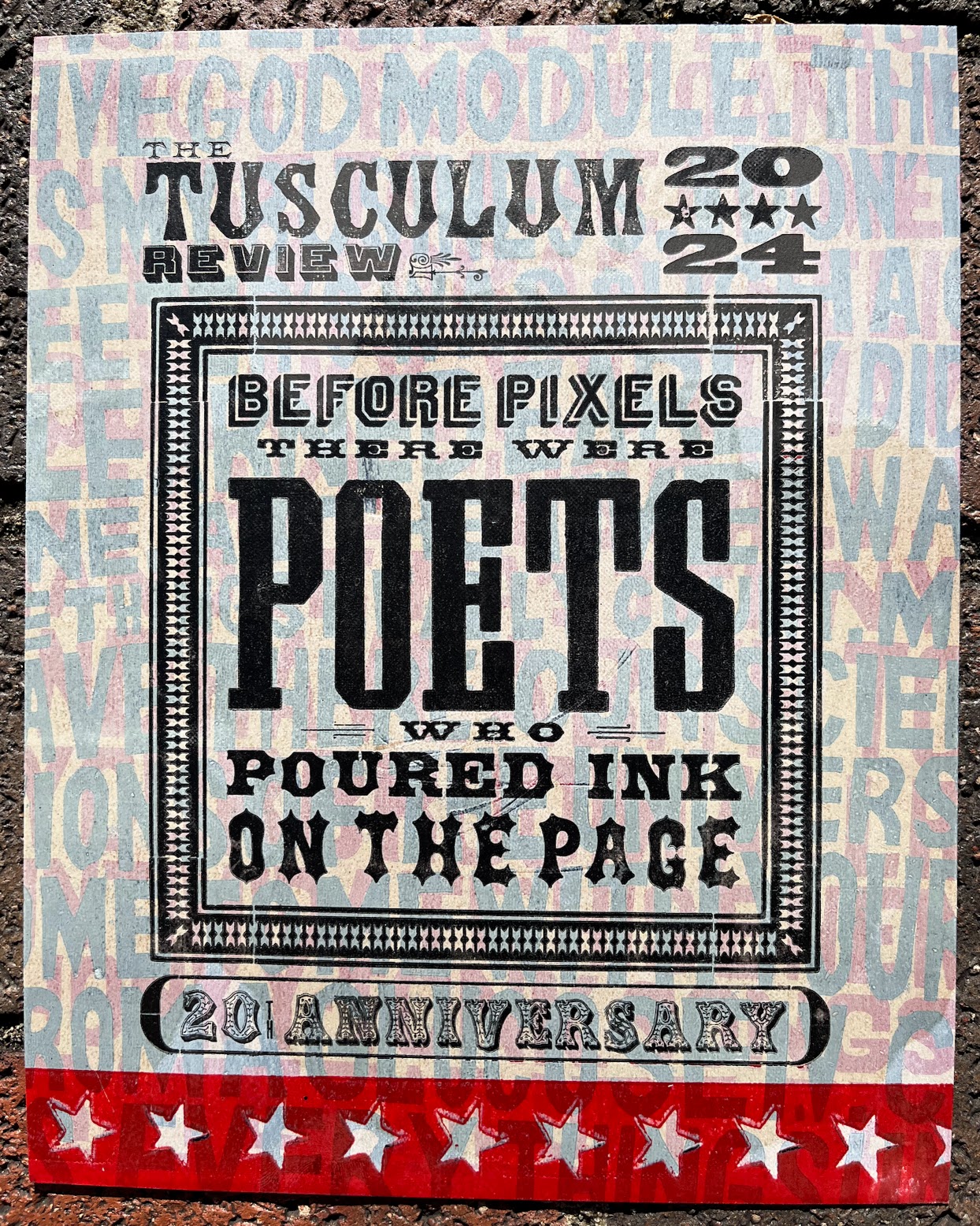

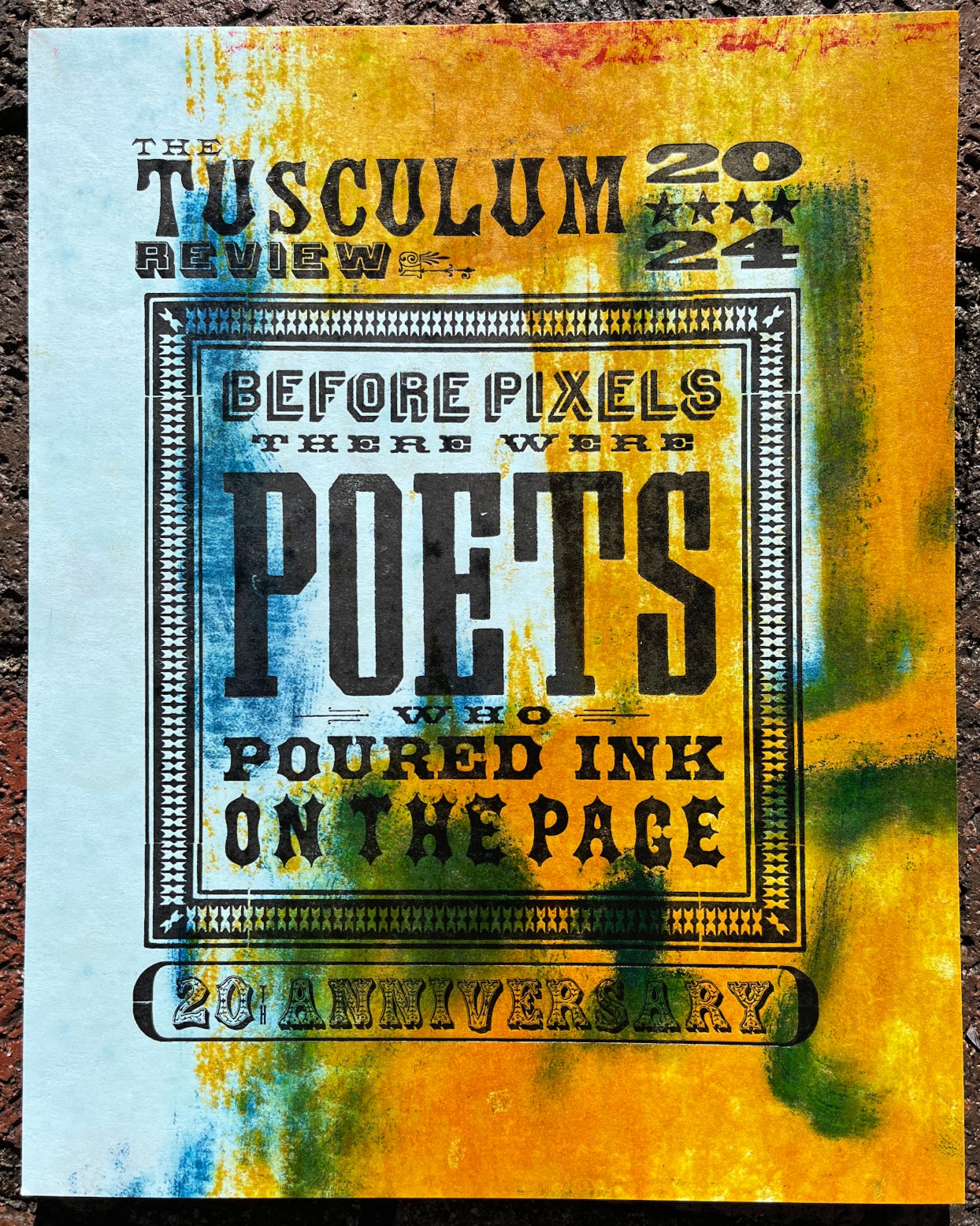

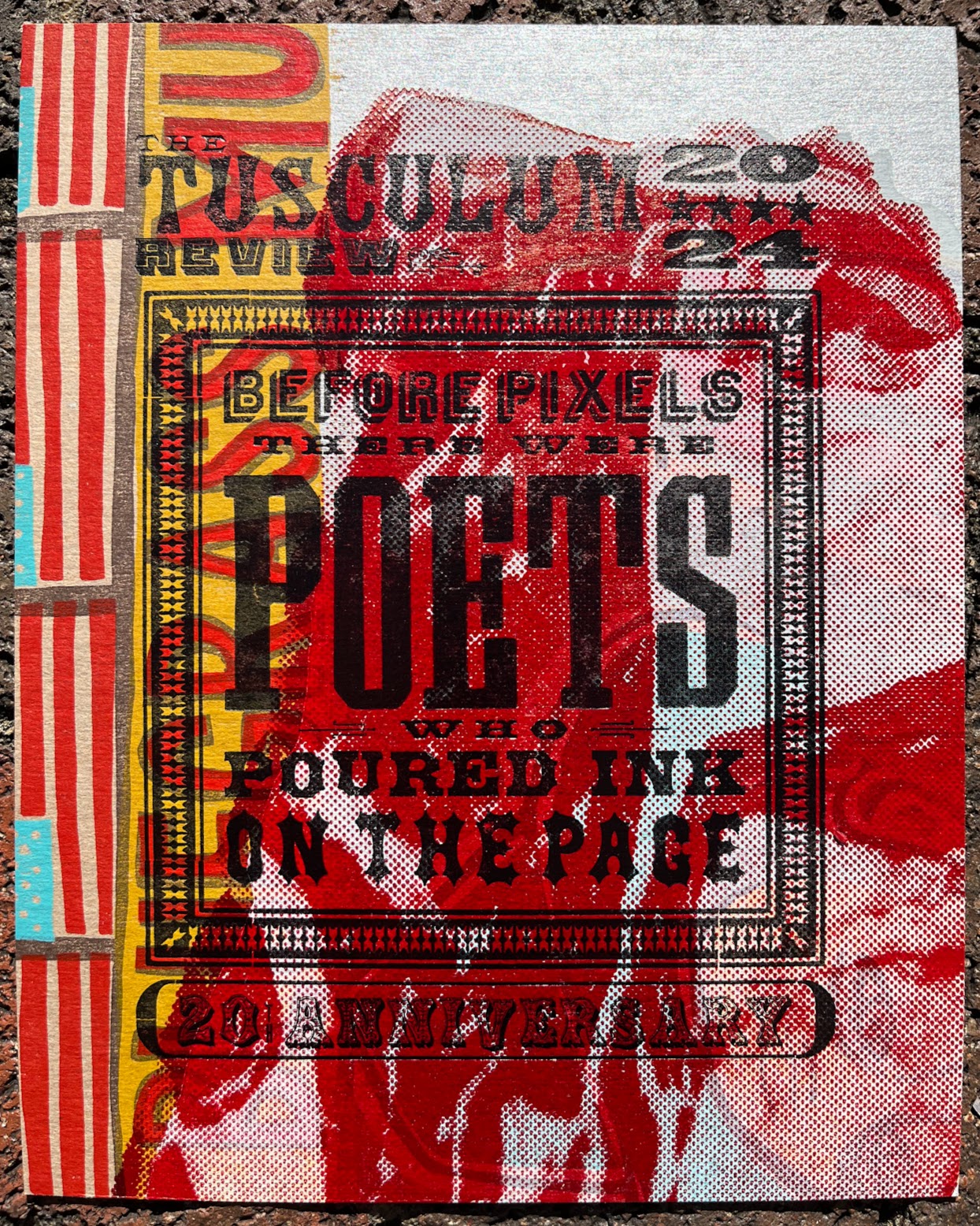

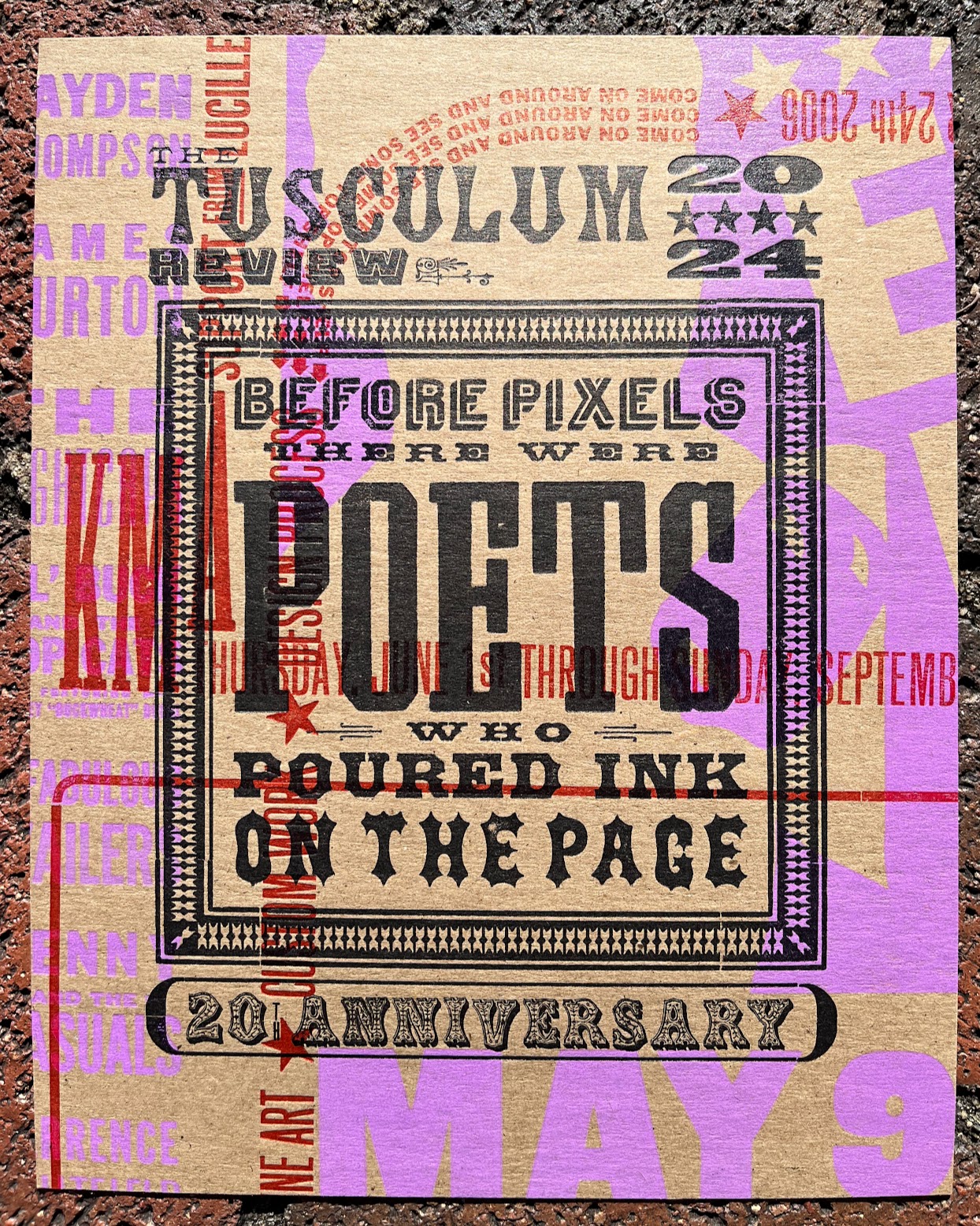

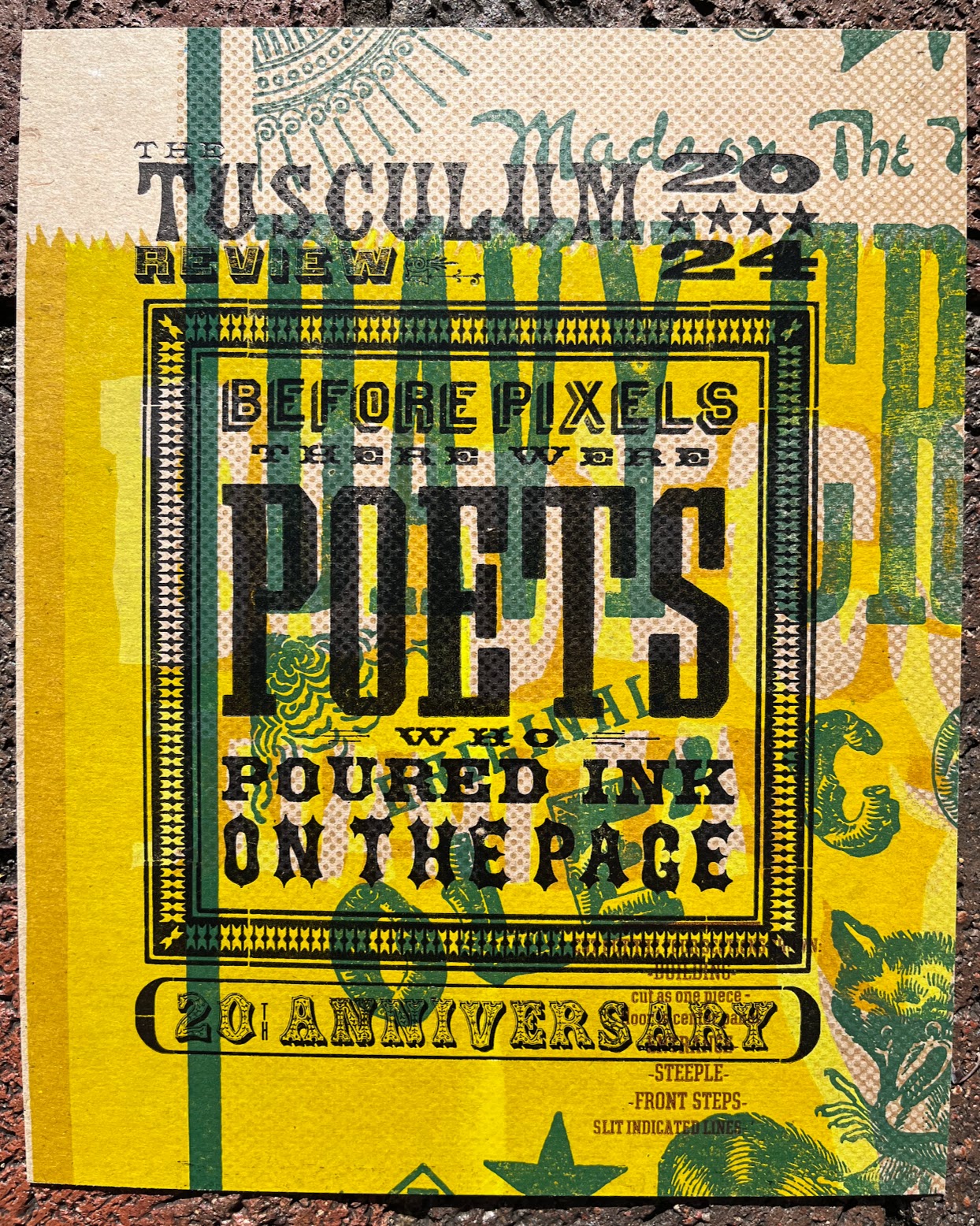

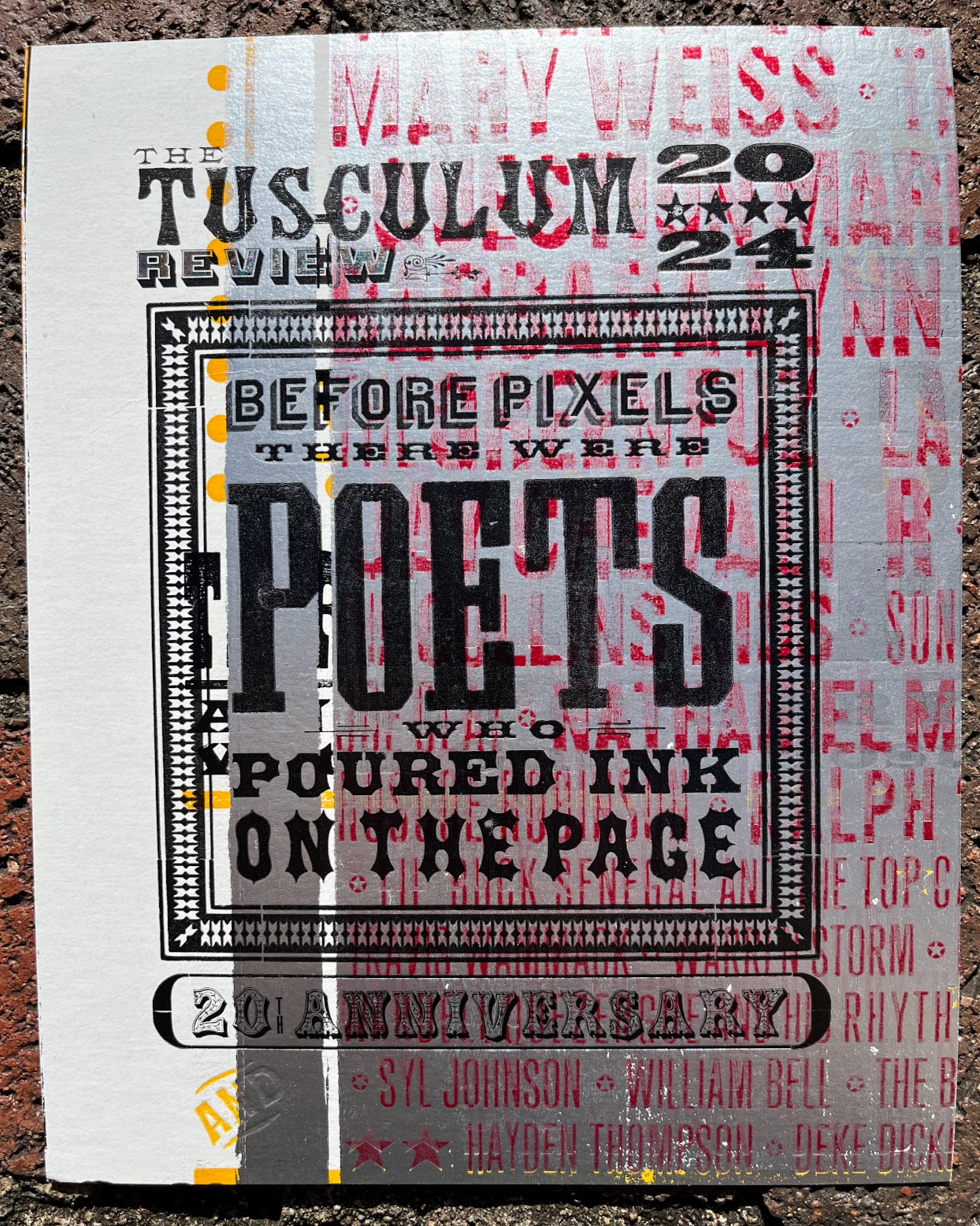

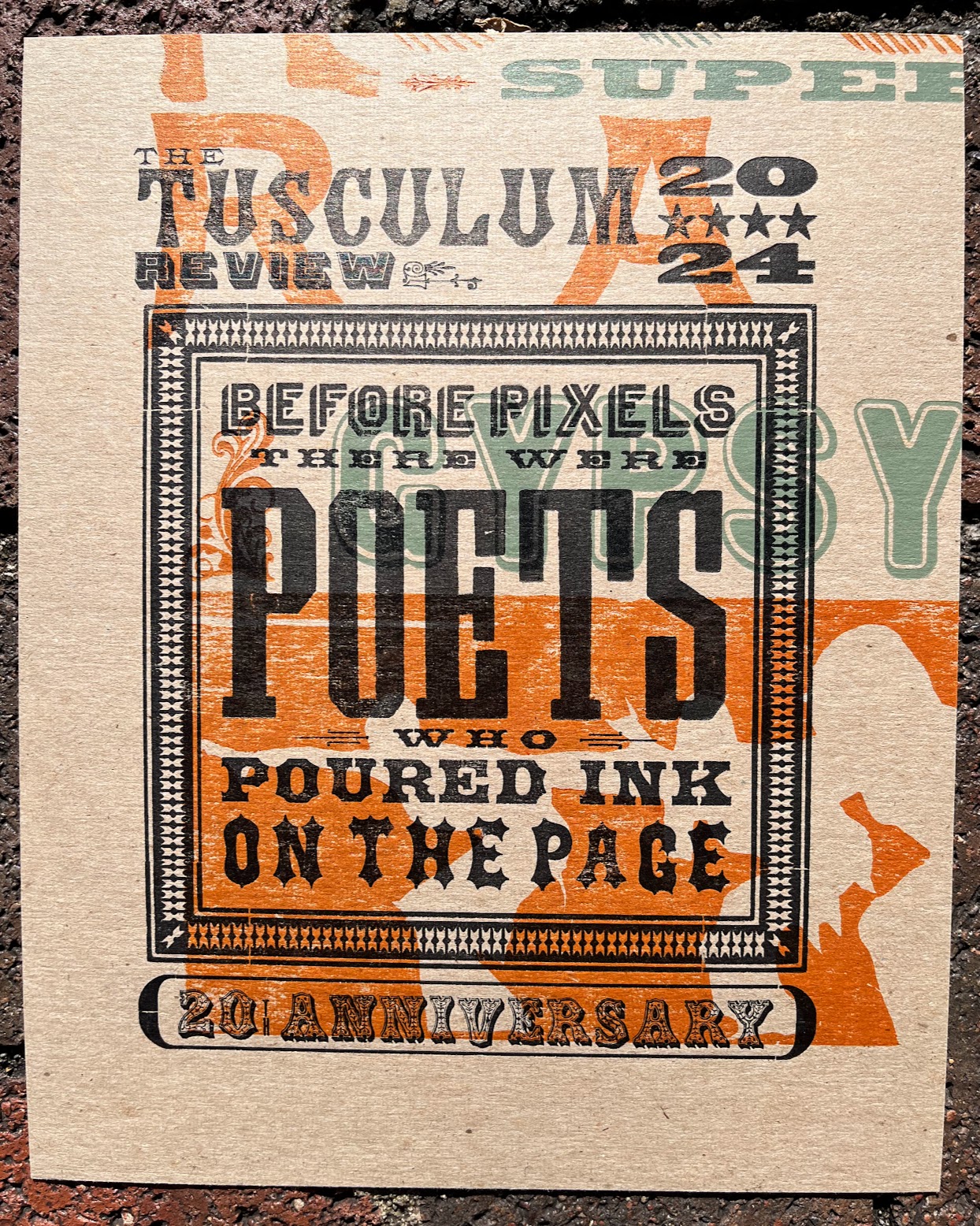

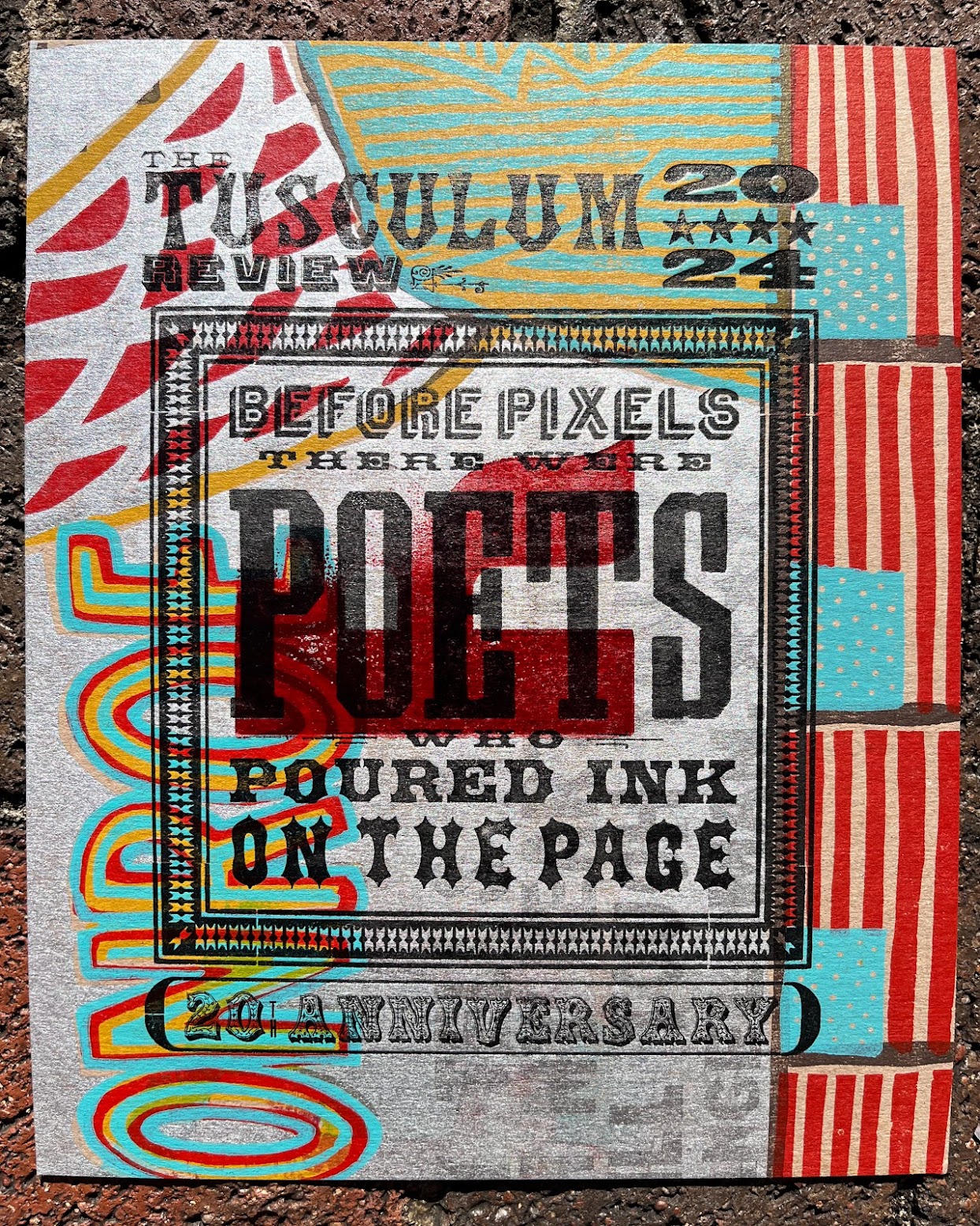

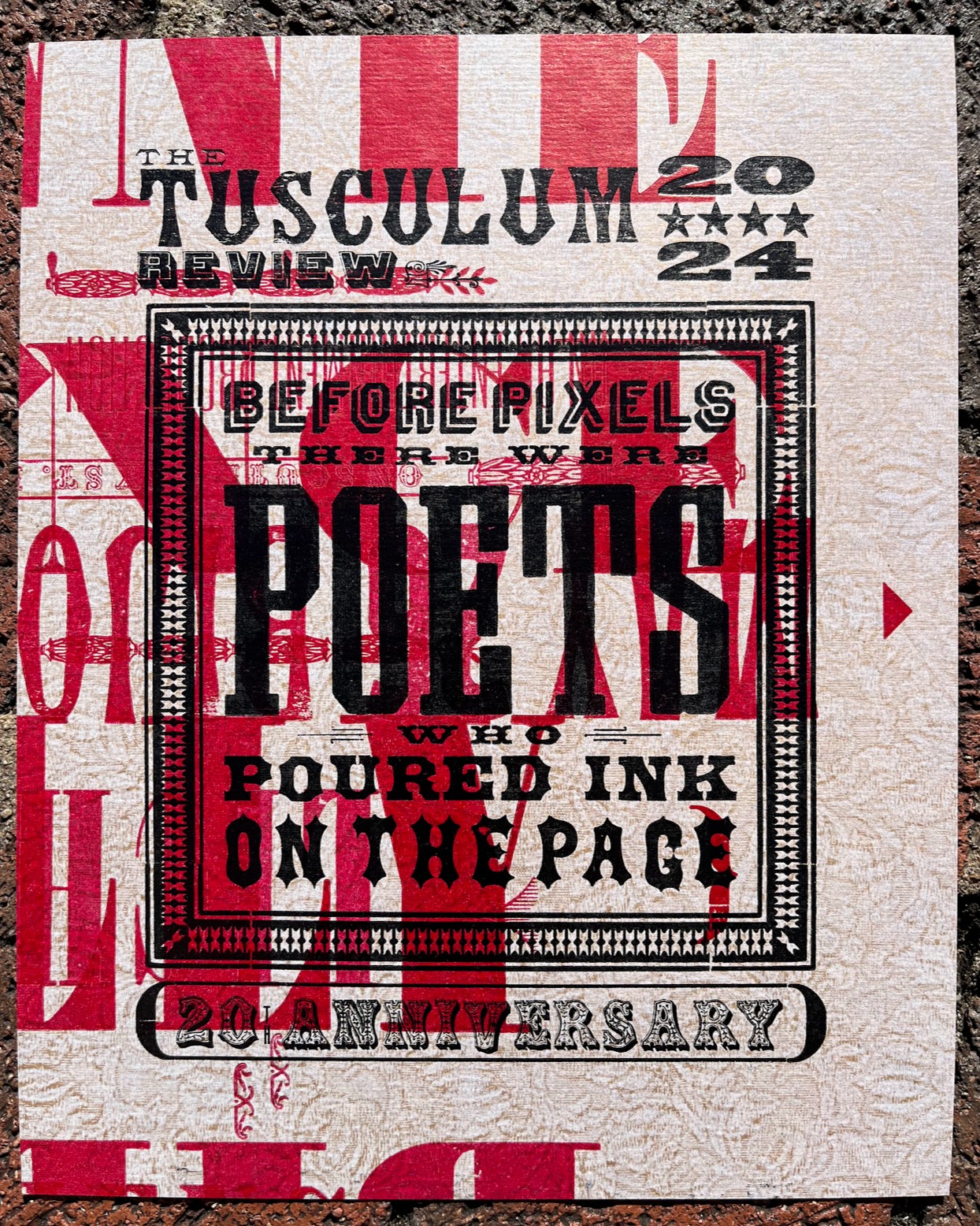

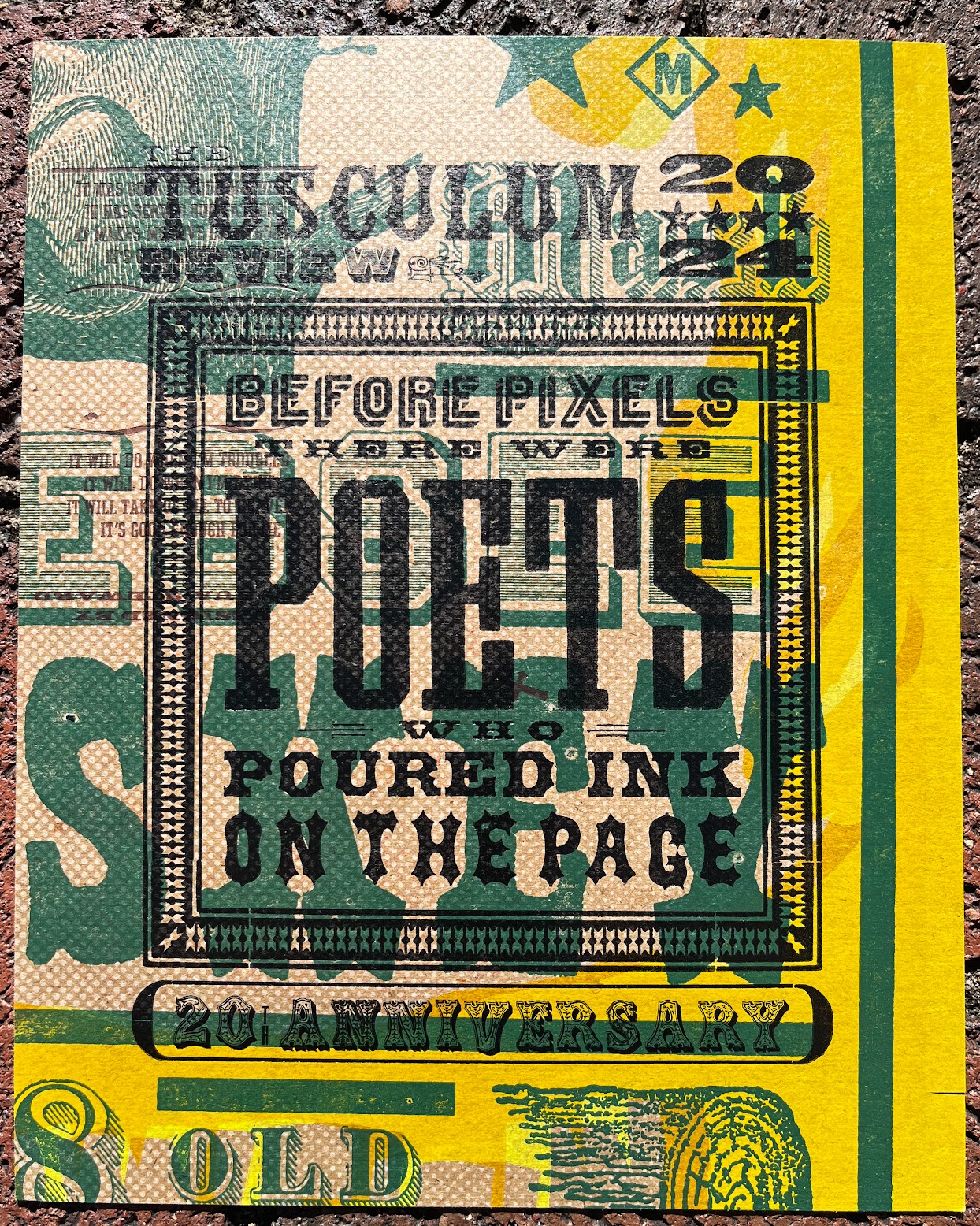

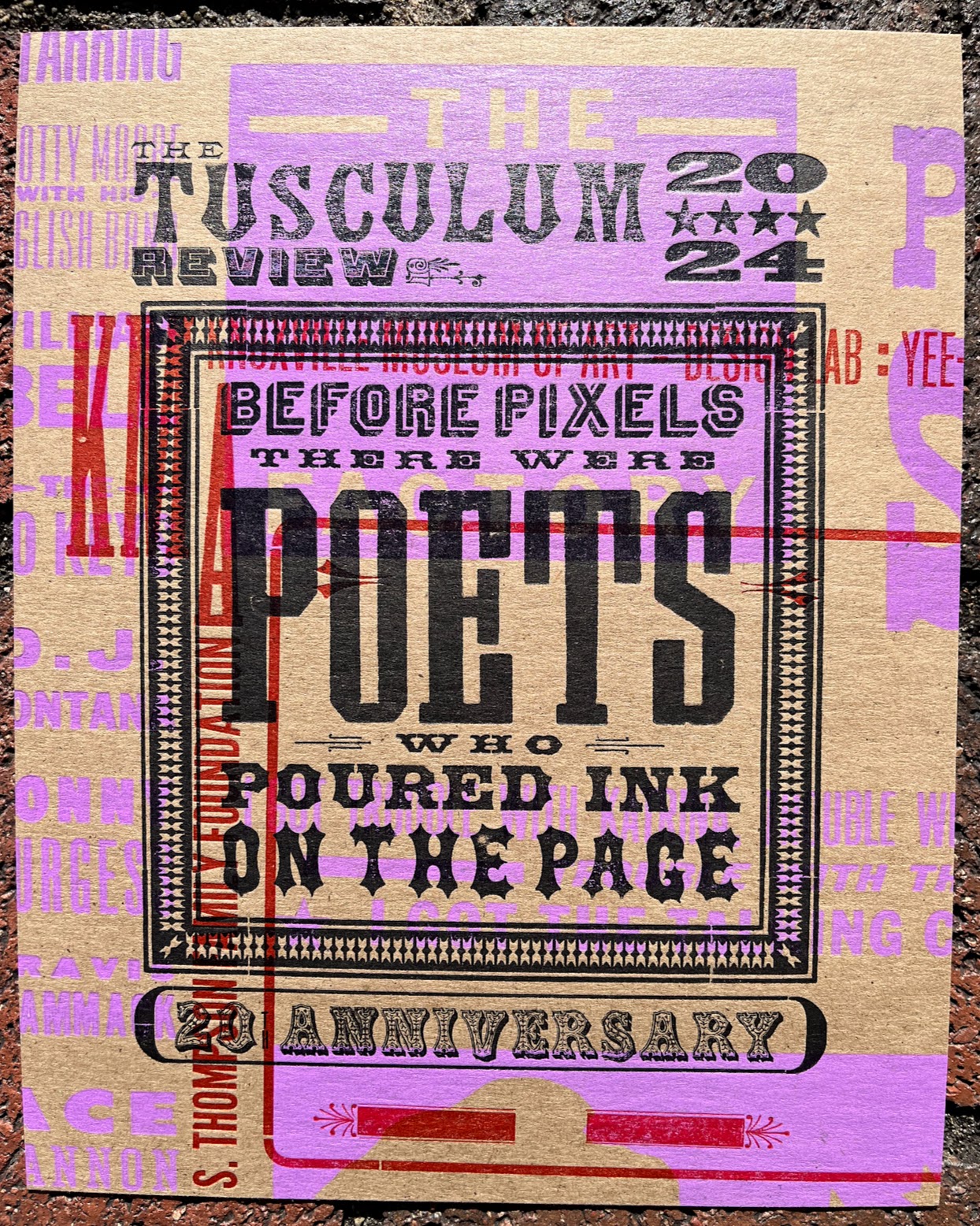

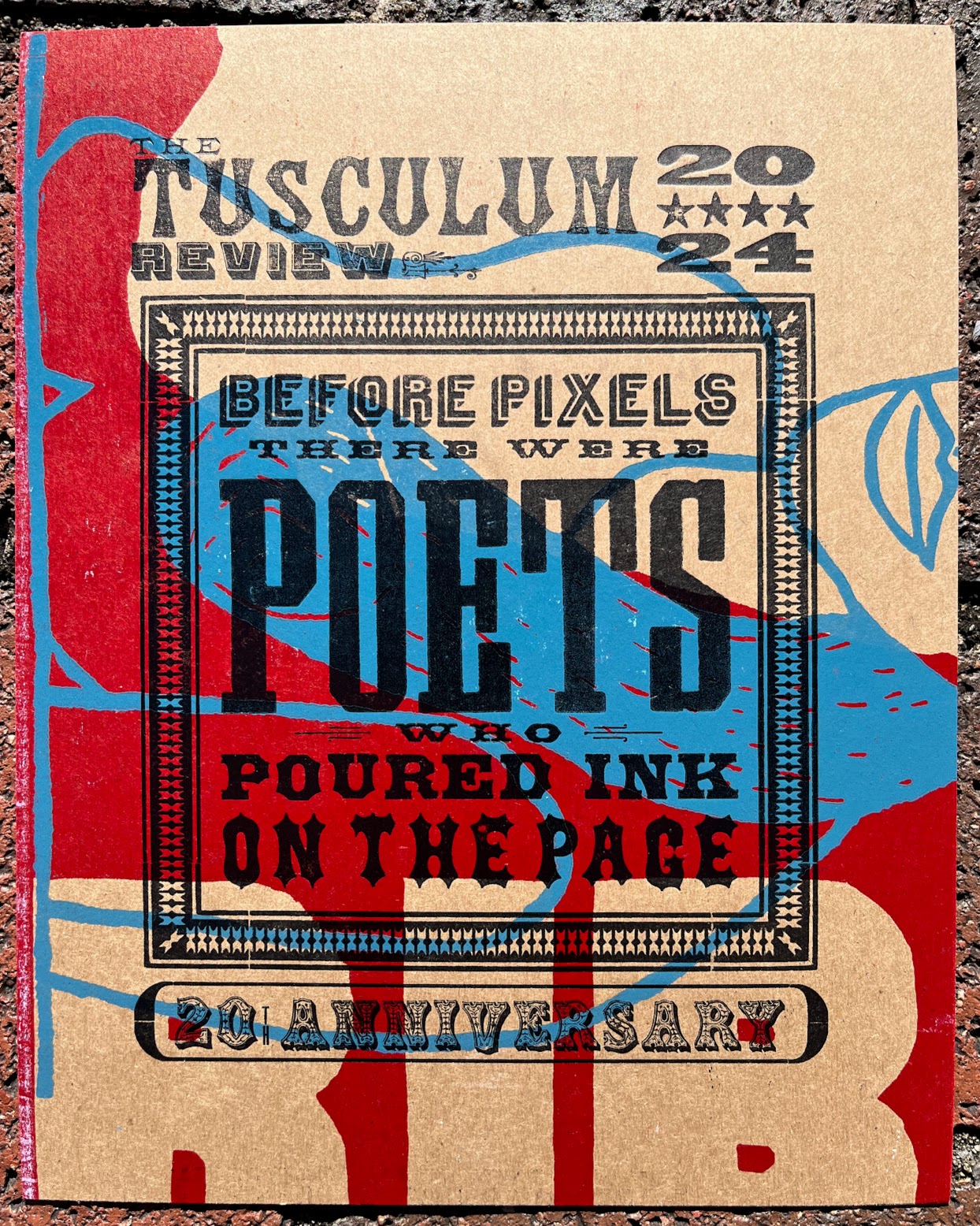

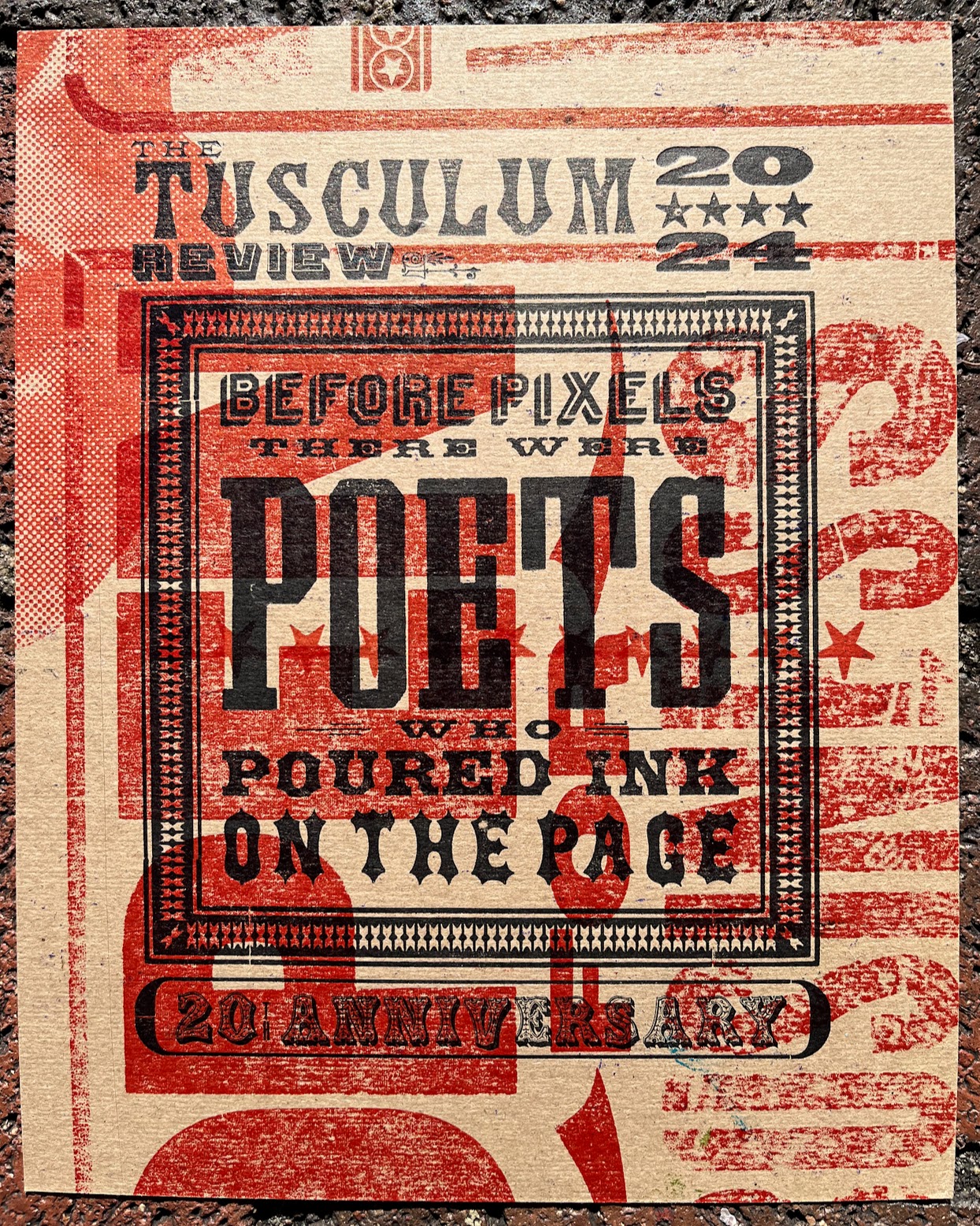

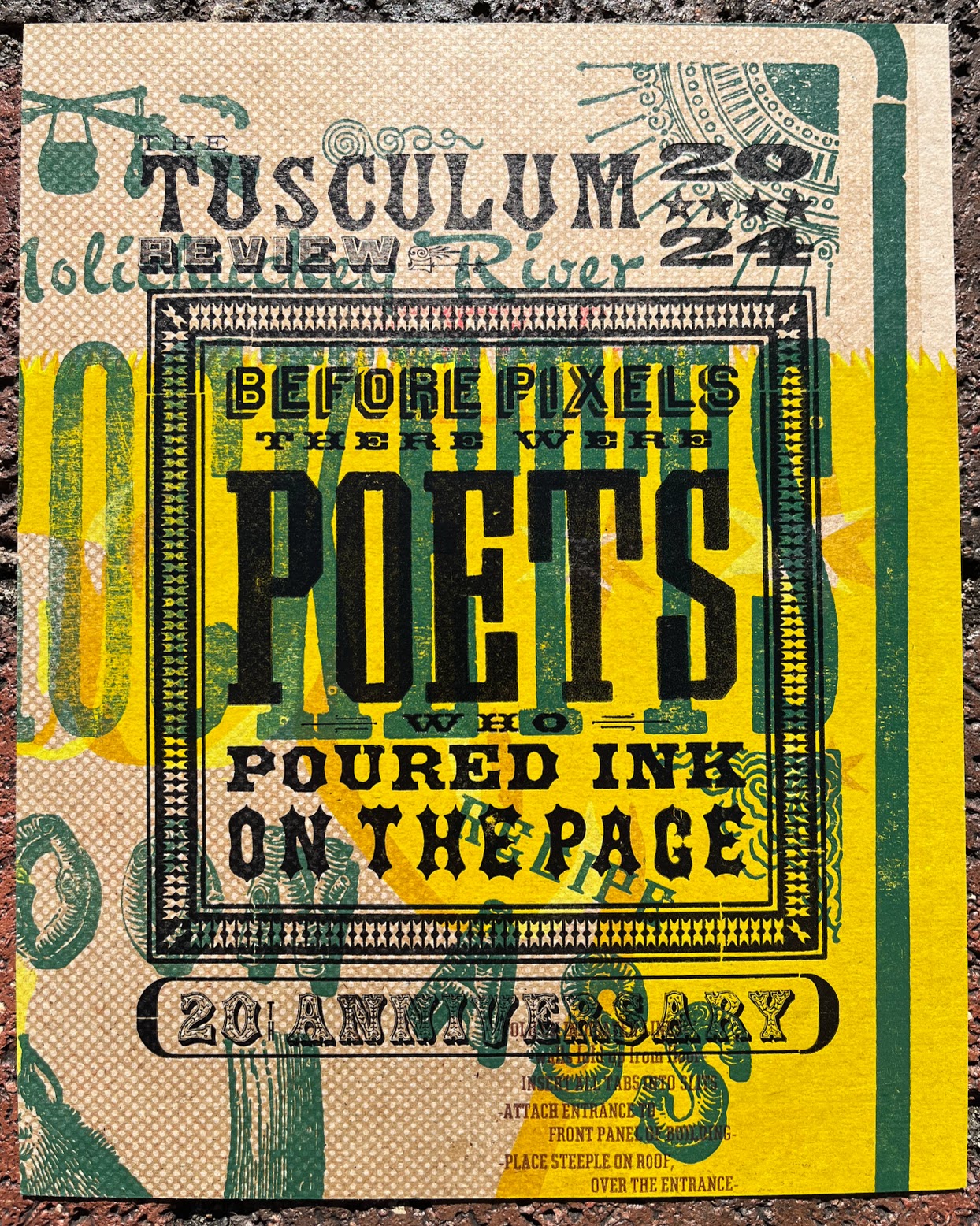

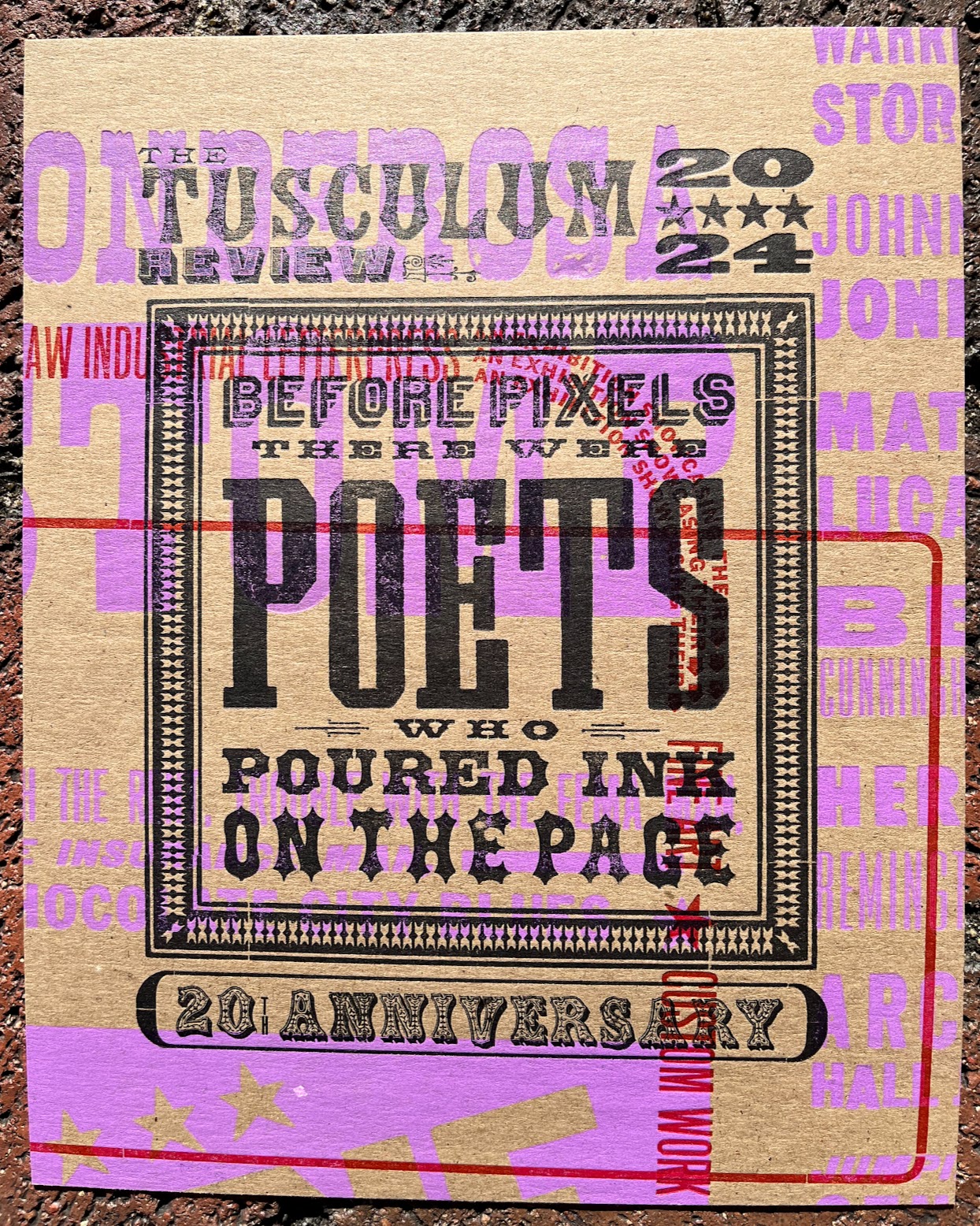

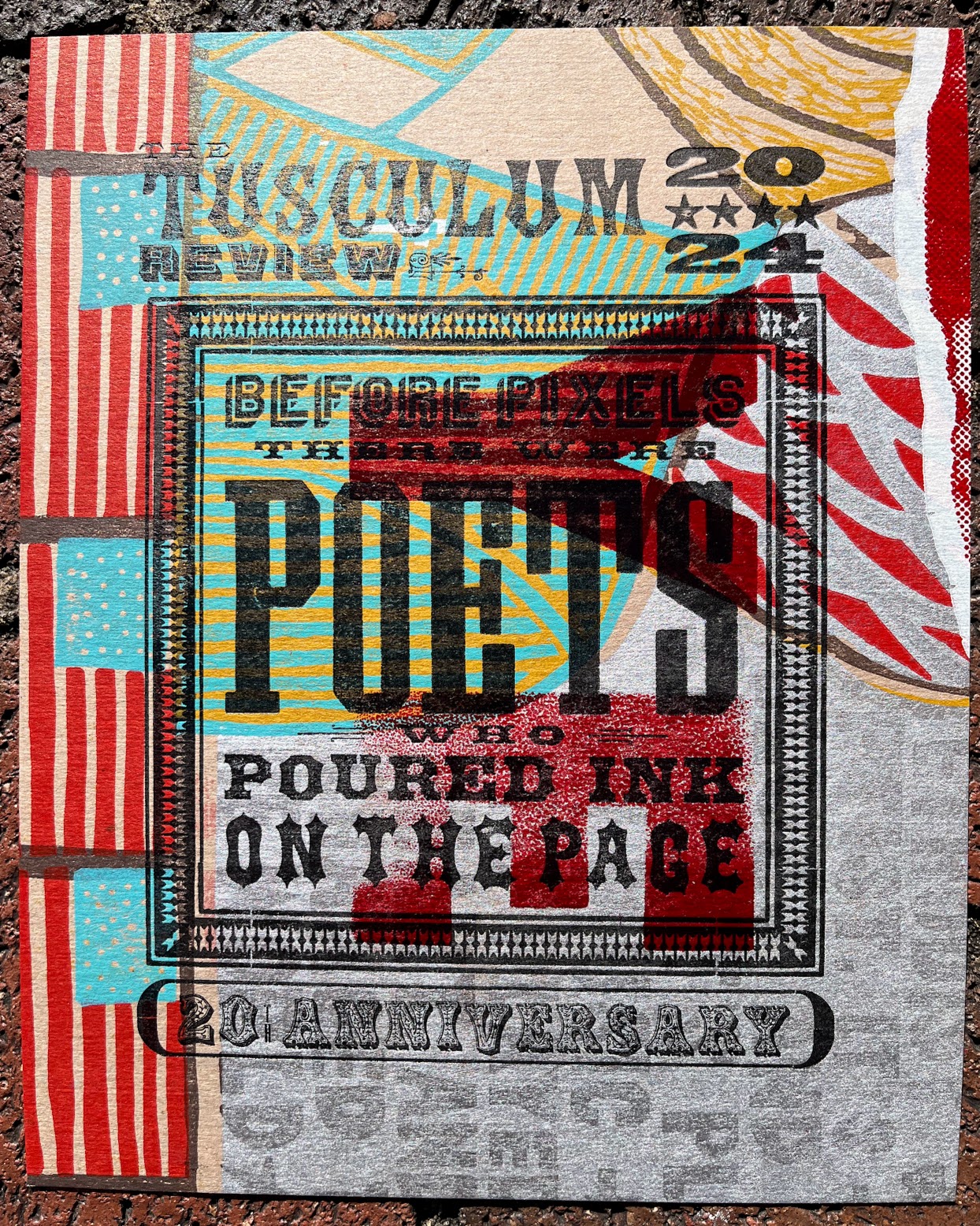

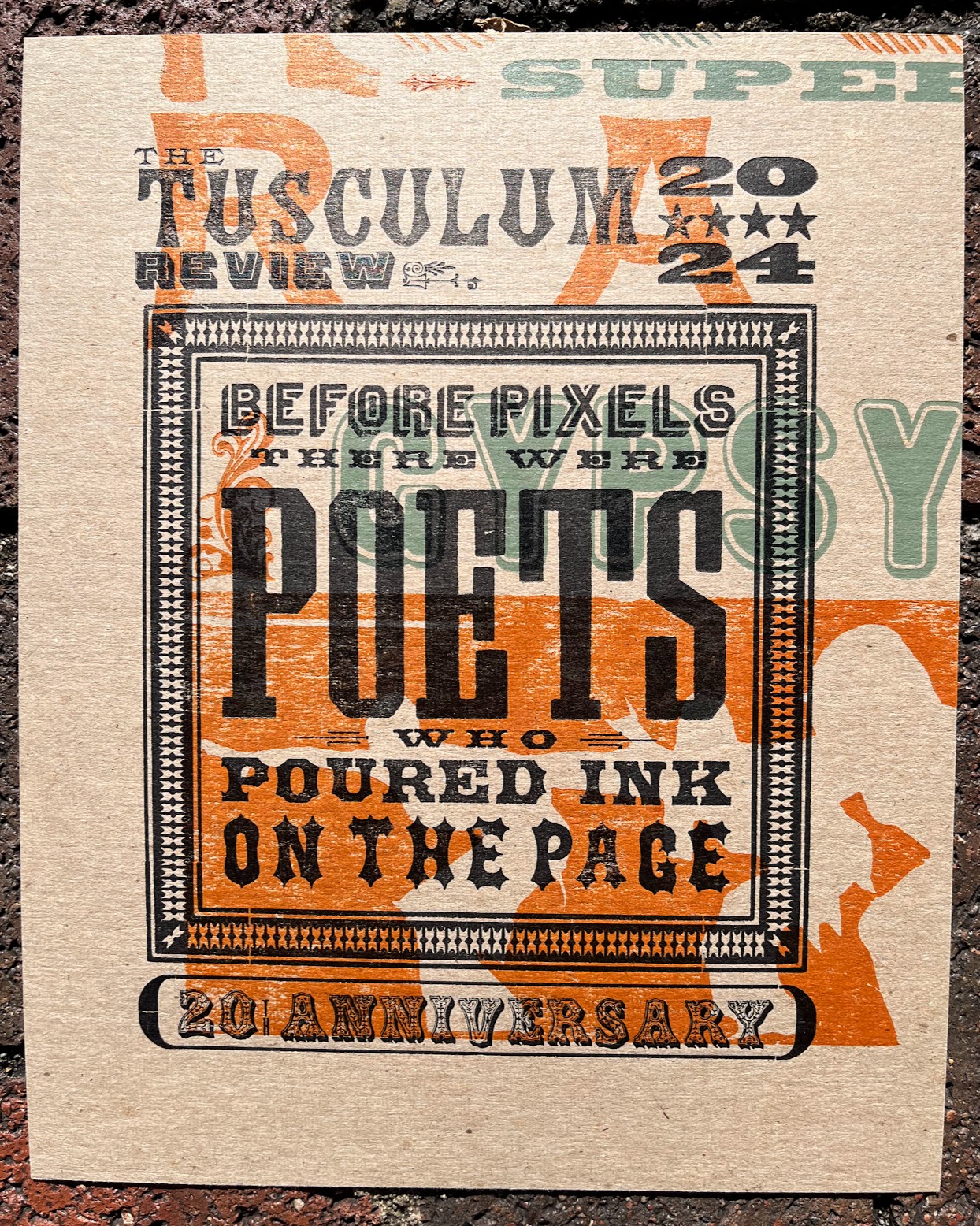

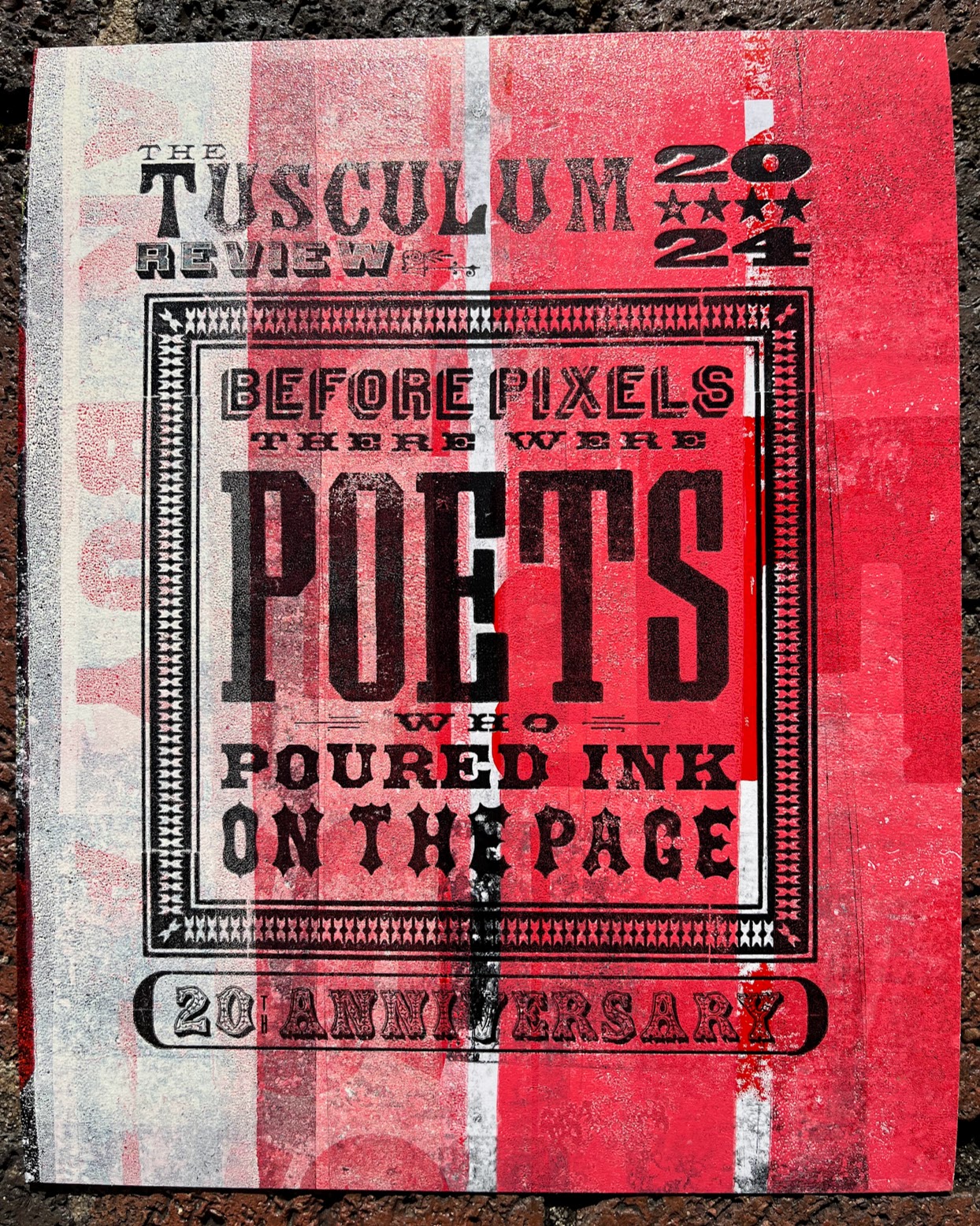

Letterpress artist Kevin Bradley, proprietor of VooDoo Rocket Institute of Higher Typographical Design, reminds us on the cover of the 20th Anniversary volume: “BEFORE PIXELS THERE WERE POETS WHO POURED INK ON THE PAGE.” The Tusculum Review, two decades in, is still doing it the old-fashioned way: curating work from across generations, cultures, and genres that draws back the curtain and points, as Whitman did, at the way life is lived now.

This issue is also significant because it marks the last issue by two foundational editors: Wayne Thomas who led the journal as Editor from 2005 to 2014, Drama Editor from 2015 to 2024, and Desirae Matherly, who served as Nonfiction Editor, in-person and later remotely, from 2009 to 2024. Both editors made the journal a container for excellent new texts and ensured their meticulous transmission. Wayne Thomas was more than Editor: he designed the journal for readability and timeless style, so back issues of The Tusculum Review remain a pleasure to read and discover. Thomas built a community of writing professors for whom students were a prioritry and student editors who believed literature was theirs to become a part of. Desirae Matherly coached undergraduate students in her Nonfiction Workshop to mature, incisive, and inventive writing: one semester every one of her students published their essays in highly-regarded journals. This is the first issue for which Poetry Editor Joshua L. Martin made all the final poetry decisions, and his undergraduate workshop students are already winning awards and publishing their work. He took over for the always-generous Clay Matthews, who, like Dr. Matherly, served remotely for many years after leaving Tusculum to teach elsewhere. During his time at Tusculum, Dr. Matthews influenced the careers of poets like Justin Phillip Reed, a 2013 Tusculum graduate who won the National Book Award for Poetry in 2018. But neither Clay, Desi, nor Wayne only mentored stars: they showed all students how writing could enhance their daily lives and how their editorial support of authors and enthusiasm for literature was a collaborative joy they could take with them into any career.

Here’s hoping for twenty more disruptive years.